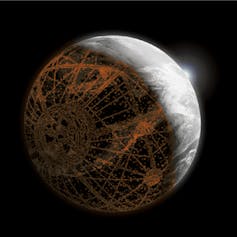

Any fan of the galaxy far, far away will have loved the newest information gleaned from The Mandalorian about life on the planet-city Coruscant. The latest instalments of Disney’s streaming series, now in its third season, have seen a new storyline take root in the galactic capital of the Star Wars universe – a planet instantly recognisable from outer space for the cog-like rings and lines of lights that completely cover its surface.

Dark Attsios/Wikimedia, CC BY

First introduced in George Lucas’s 1997 special edition of Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, Coruscant is an iconic world. Up close, it presents an impossibly dense planetary cityscape. Streams of airborne traffic travel between endless high-rise mega-structures. These literally reach for the sky, their elevation covering more than 5,000 levels – from the criminal underworld to the upper strata inhabited by the politically powerful.

Strikingly, this built environment is completely disconnected from the planet’s natural systems. In the latest episode of the Mandalorian, an ex-imperial officer shows a newly arrived scientist around a public square. She tricks him into trying to touch what looks like a landscaped boulder, only for him to rebuked by a flying police droid. The rock is, in fact, the peak of Umate, the planet’s tallest mountain. “They say it’s the only place on the entire surface where you can see the planet itself,” the officer reveals.

Shane Crotty/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Coruscant, the scientist had learnt earlier, is one of only a handful of city-planets in the galaxy. “It is known as an ecumenopolis,” a digital voice explains.

This term, coined by Greek architect and urban planner Constantinos Doxiadis in the early 1960s, means “planet-spanning city”. For Coruscant, it is the perfect descriptor. If it has proven a less accurate predictor for urban expansion on Earth, the world-devouring nature of Coruscant’s urban sprawl presents, nonetheless, a cautionary tale.

How the idea of an ecumenopolis came about

In the era of the Star Wars saga in which the Mandalorian story is set, Coruscant is the political and economic centre of the New Republic. A well-managed, democratic, free and peaceful world, it is nonetheless constrained by unwieldy bureaucracy and stark social inequalities dividing those in the higher and lower levels.

The city-planet has an estimated population of 3 trillion residents, which works out at 430 times the Earth’s current population of 8 billion. This demographic comparison is instructive.

Doxiadis was part of a cosmopolitan generation of 20th-century urbanists – also including French philosopher Henri Lefebvre and Brazilian geographer Milton Santos – whose social and spatial theory encompassed continental and even planetary scales. Doxiadis based his thinking on everything from the individual home to worldwide infrastructure.

When he wrote about the “universal city” of the 21st century in 1962, he extrapolated the growth rates of the time to predict that the world’s population could reach 50 billion by the year 2100. He forecast that 98% would be urban residents, spread over a total surface of 48 million sq km – the equivalent of about a third of the Earth’s land surface.

As early as the late 1920s, the American historian and influential urban architecture specialist Lewis Mumford had feared that the expansive modern metropolis of the early 20th century was giving way to a monstrous megalopolis. In his 1961 book, The City in History, he took the idea even further.

Mumford argued that this unrelenting expansion – the megalopolis’s “profoundly disastrous success” – would exploit its surrounding territories for resources, while fostering chaos and violence within. This, he said, would eventually lead to the city’s abandonment. He predicted the demise in an era of what he termed “the necropolis”: the city of death.

Natalya Letunova/Unsplash, CC BY

Doxiadis shared Mumford’s fears, but he was less concerned with the collapse of western civilisation. On the contrary, he thought that, provided the right network of transport and communications were built alongside new settlements to support the ecumenopolis’s growth, its megalopolitan expansion would result in a “city of life”.

Doxiadis’s research and practice espoused the optimistic belief that urban expansion, both demographic and physical, could be scientifically managed in proper balance “with the survival of open spaces”. In other words, the ecumenopolis he envisaged was enormous, but it was not planet-wide.

How our world is more than urban

We might only be in the early stages of the 21st century, but the urban-rural balance of the world has already tipped towards cities. By 2050, the UN’s Population Division predicts that over two-thirds (68%) of the world’s population will be concentrated in urban centres. This represents a complete reversal of the rural-urban population distribution of just a century ago. And by 2100, this ratio could top 85%.

Doxiadis correctly foresaw this urban transition en masse. In terms of total population size, however, we are still light years away from what he envisaged in the 1960s.

Since the publication in 1972 of The Limits to Growth, the landmark report led by American environmental scientist Donella Meadows, our understanding of the factors limiting urban demographic, economic and physical expansion has sharpened. Scientists term these planetary boundaries.

For some fans, Coruscant is the original home world of humanity in the Star Wars galaxy. In our own, however, were the Earth to ever actually be subsumed into a single cityscape, the resulting ecumenopolis would collapse under the weight of its ecological footprint.

Excessive land-system change or freshwater consumption, among other things, would increase the risk of irreversible environmental change. And if such planetary boundaries were crossed, humanity would simply not be able to survive, let alone thrive like Coruscanti society does.

From a global justice perspective, it is not enough to acknowledge that we live at a time of unprecedented planetary urbanisation. We must find ways to curb the predatorial tendencies that urbanisation has of devouring the wider world. We need to protect what is left of the Earth – and come up with better alternatives to the modern capitalist city as the paragon of human settlement.