The BBC recently reported on a disturbing new form of cyberbullying that took place at a school in Almendralejo, Spain.

A group of girls were harmed by male classmates who used an app powered by artificial intelligence (AI) to generate “deepfake” pornographic images of the girls, and then distributed those images on social media.

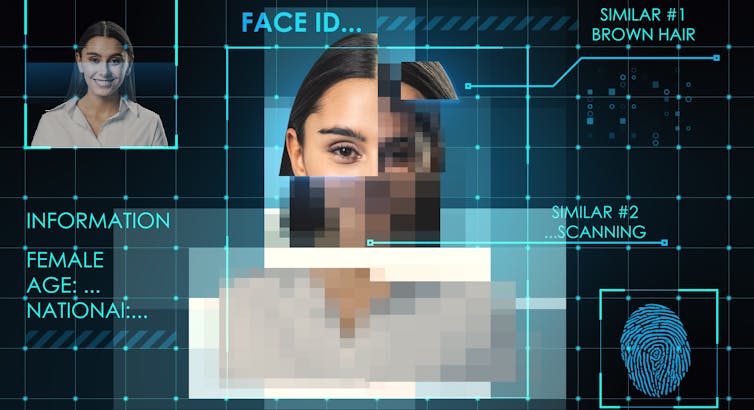

State-of-the-art AI models can generate novel images and backgrounds given three to five photos of a subject, and very little technical knowledge is required to use them. While deepfaked images were easier to detect a few years ago, today, amateurs can easily create work rivalling expensive CGI effects by professionals.

The harms in this case can be partially explained in terms of consent and privacy violations. But as researchers whose work is concerned with AI and ethics, we see deeper issues as well.

Read more:

How to combat the unethical and costly use of deepfakes

Deepfake porn cyberbullying

In the Almendralejo incident, more than 20 girls between 11 and 17 came forward as victims of fake pornographic images. This incident fits into larger trends of how this technology is being used. A 2019 study found 96 per cent of all deepfake videos online were pornographic, prompting significant commentary about how they are being specifically used to degrade women.

The political risks of deepfakes have received high-profile coverage, but as philosophy researchers Regina Rini and Leah Cohen explore, it is also relevant to consider deeper personal harms.

Legal scholars like Danielle Keats Citron note it is clear society “has a poor track record addressing harms primarily suffered by women and girls.” By staying quiet and unseen, girls might escape becoming victims of this new and cruel form of cyberbullying.

We think it is likely this technology will create additional barriers for students — especially girls — who may miss out on opportunities due to the fear of calling attention to themselves.

Used as tool for misogyny

Philosopher Kate Manne provides a helpful framework for thinking about how deepfake technology can be used as a tool for misogyny. For Manne, “misogyny should be understood as the ‘law enforcement’ branch of a patriarchal order, which has the overall function of policing and enforcing its governing ideology.”

That is, misogyny polices women and girls, discouraging them from taking traditionally male-dominated roles. This policing can come from others, but it can also be self-imposed.

Read more:

Trolling and doxxing: Graduate students sharing their research online speak out about hate

Manne explains there are punishments for women perceived as resisting gendered norms and expectations. External policing of misogyny involves the disciplining of women through various forms of punishment for deviating from or resisting gendered norms and expectations.

Women can be denied a career opportunity, harassed sexually or harmed physically for not living up to gendered expectations. And now, women can be punished through the use of deepfakes. The patriarchy has another weapon to wield.

When considering Manne’s notion of male entitlement, we can predict instances of this policing occurring if female students are offered positions male students deem they are entitled to, such as winning the student council elections or receiving academic awards in traditionally male-dominated fields.

(Shutterstock)

A ‘joke’?

The technology of deepfakes is a very accessible weapon to wield in these cases, and one that can cause a lot of harm. The shame and threat to personal safety are already evident. Cultural misogyny additionally harms by trivializing this experience: he can still say it is just a joke, that she is taking it too seriously and she shouldn’t be hurt by it because it isn’t real.

Self-imposed policing can be reinforced through deepfakes and other image manipulative technology. Knowing that this form of cyberbullying is available can lead to self-censoring.

Students who are visible in public leadership have more likelihood of being deepfaked; these students are known by more people in their school communities and are scrutinized for public roles.

Will we become more used to them?

It could be that once these deepfakes become more common, people will be less surprised to see these images and videos, so they will not be as scandalous to others and embarrassing to the victim.

Yet, philosophy scholar Keith Raymond Harris discusses how people can make psychological associations even when they know they are basing these on false content. These associations, even if they may not “rise to the level of belief” can be classified as a harm of deepfakes.

That means that when students make deepfakes of their classmates, it can alter their perception of their targets and cause further real-life mistreatment, harassment and disrespect.

It means that boys are less likely to consider their peers, who are girls, as capable students deserving of opportunities. The use of this technology amongst peers in schools risks damaging girls’ confidence through the sexist education environment that this technology will enforce.

Another tool for ‘typecasting’ girls

Manne’s analysis also suggests how even if a girl does not have a deepfake of her made directly, deepfakes can still impact her. As she writes, “women are often treated as interchangeable and representative of a certain type of woman. Because of this, women can be singled out and treated as representative targets, then standing in imaginatively for a large swath of others.”

Girls are often classified into types in this way, from the ‘80s “Valley Girl,” the millennial notion of the “basic bitch” to Gen Z classifications of “VSCO-Girl,” (named from a photo editing app) or a “Pick-Me Girl.”

When these psychological associations made of a particular woman lead to misogynistic associations of all women, misogyny will be further enforced.

(Shutterstock)

Lampooning, shunning, shaming women

Manne explains that misogyny does not solely manifest through violent acts, but “women [can]… be taken down imaginatively, rather than literally, by vilifying, demonizing, belittling, humiliating, mocking, lampooning, shunning and shaming them.”

In the case of deepfakes, misogyny appears in this non-physically violent form. Still, in Almendralejo, one parent interviewed for the story rightly classified the artificial nude photos of the girls distributed by their classmates “an act of violence.”

We doubt this technology is going away. Understanding how deepfakes can be used as a tool for misogyny is an important first step in considering the harms they will likely cause, and what this may mean for parents, children, youth and schools addressing cyberbullying.