risks, building resilience and accelerating research, there is every reason to dream of a malaria-free future”.

Lifesaving bednets

In 2020, more insecticide treated bednets (ITNs) – the primary defense in most malaria-endemic countries – were distributed than in any year on record.

And distributions in 2021 were strong overall, similar to pre-pandemic levels.

However, Benin, Eritrea, Indonesia, Nigeria, Solomon Islands, Thailand, Uganda, and Vanuatu distributed less than 60 per cent of their ITNs and Botswana, Central African Republic, Chad, Haiti, India, Pakistan and Sierra Leone did not dispense any.

Tracking other interventions

In 2021, seasonal malaria chemoprevention – a highly effective, community-based intervention – reached nearly 45 million children in 15 African countries, which was a substantial increase from 33.4 million in 2020 and 22.1 million in 2019.

And despite supply chain and logistical challenges during COVID, a record number of rapid diagnostic malaria tests were distributed to health facilities in 2020.

An estimated 242 million artemisinin-based combination therapies – the most effective treatment for P. falciparum malaria – were delivered worldwide in 2021 compared to 239 million in 2019.

Insecticide treated bednets (ITNs) are the primary vector control tool used in most malaria-endemic countries. The WHO report compares two years of distribution levels.

Convergence of threats

Despite successes, challenges continued and led the statistical field, particularly in Africa, which shouldered about 95 per cent of cases and 96 per cent of deaths worldwide in 2021.

Disruptions during the pandemic and converging humanitarian crises, health system challenges, restricted funding, rising biological threats and a decline in the effectiveness of core disease-cutting tools, threatened the global response.

“Despite progress, the African region continues to be hardest hit by this deadly disease”, said WHO Regional Director for Africa Matshidiso Moeti, noting that news tools and the funding to deploy them are “urgently needed to help us defeat malaria”.

Malaria funding in 2021 stood at $3.5 billion, an increase from the two previous years but well below the estimated $7.3 billion required globally to stay on track.

Other obstacles

At the same time, a decline in the effectiveness of key malaria control tools, most crucially ITNs, is impeding further progress against malaria.

Among the threats are insecticide resistance, insufficient access, and loss of ITNs due to the stresses of daily use outpacing replacement.

Other rising risks involve parasitic mutations affecting rapid diagnostic tests; growing parasite resistance to malaria drugs; and an invasion of an insecticide-resistant mosquito.

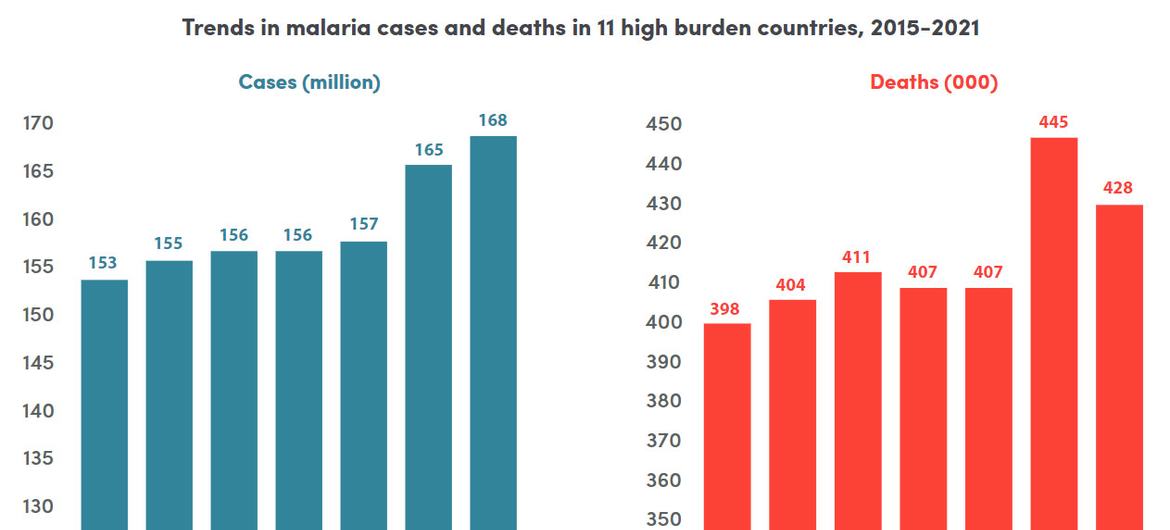

Trends in malaria cases and deaths in 11 high burden countries, between 2015 and 2021.

New avenues of hope

For African countries to build a more resilient response, WHO recently launched a strategy curbing antimalarial drug resistance and an initiative stopping the spread of the Anopheles stephensi malaria vector.

Additionally, a new global framework to respond to malaria in urban areas, developed jointly by WHO and UN-Habitat, provides guidance for city leaders and malaria stakeholders.

Meanwhile, a robust research and development pipeline is set to bring a new generation of malaria control tools that could help accelerate progress towards global targets, including long-lasting bednets with new insecticide combinations; spatial repellents; and genetic engineering of mosquitoes.

Also in the pipeline are new diagnostic tests, next-generation medicines to combat drug resistance, and other malaria vaccines.

According to the report, malaria-endemic countries should continue use a primary healthcare approach to strengthen health systems and ensure quality services and interventions for everyone in need.

Infant in Ghana protected from malaria by a bednet.