Earlier this year, China issued new rules on religious activity that tighten oversight of clergy and congregations.

The rules are part of a long-standing strategy by the Chinese government to align religion with communism and ensure loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which espouses and promotes atheism. More recently, such rules have also been intended to bring religion in line with traditional Chinese culture and with “Xi Jinping Thought,” the Chinese leader’s blend of Marxism and nationalism.

China’s constitution says ordinary citizens enjoy “freedom of religious beliefs” and the government officially recognizes five religions: Buddhism, Catholicism, Islam, Protestantism and Daoism (also called Taoism). But authorities closely police religious activity. China has ranked among the world’s most restrictive governments every year since Pew Research Center began tracking restrictions on religion in 2007.

Here are 10 things to know about how the Chinese government regulates religion, from our recent report, “Measuring Religion in China.”

China is pursuing a policy of “Sinicization” that requires religious groups to align their doctrines, customs and morality with Chinese culture. The campaign particularly affects so-called “foreign” religions – including Islam as well as Catholicism and Protestantism – whose adherents are expected to prioritize Chinese traditions and show loyalty to the state.

Sinicization takes various forms. Authorities have removed crosses from churches and demolished the domes and minarets of mosques to make them look more Chinese. Pastors and imams have reportedly been asked to focus on religious teachings that reflect socialist values. The government also plans to issue a newly annotated version of the Quran that will help Islamic teachings align with “Chinese culture in the new era.”

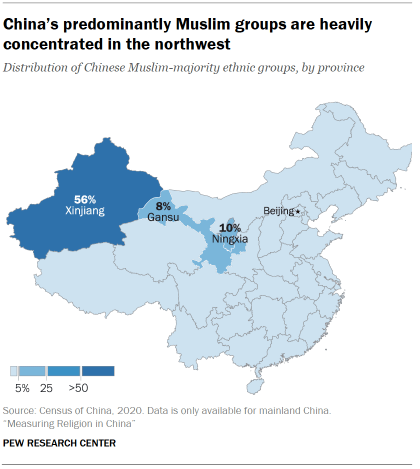

China’s restrictive policies toward Muslims – particularly Uyghurs in Xinjiang province – have been documented widely over the past decade. Human rights groups accuse China of subjecting Uyghurs to mass internment, surveillance and torture. The U.S. State Department has described events in Xinjiang as genocide, alleging that Chinese authorities have detained more than 1 million Chinese Muslims in specially built internment camps. Uyghurs make up 43% of Chinese Muslims.

China’s government rejects the accusations and says that relocations, camps and other forced measures are meant to improve Muslims’ lives. For example, Chinese officials have said camps in Xinjiang offer vocational training and counter religious extremism.

Christianity in China is governed by several sets of rules. Christians are allowed to worship in “official churches” registered with supervisory government agencies responsible for Protestantism and Catholicism. However, many Christians refuse this oversight and worship in underground churches.

Since Xi came to power in 2013, the government has banned evangelization online, tightened control over Christian activities outside of registered venues, and shut down churches that refuse to register. Authorities have also arrested prominent church leaders and some Christians reportedly have been held in internment camps.

In 2018, the Vatican and China signed an agreement over bishop appointments to help alleviate tensions for China’s Catholics – a deal that was criticized by many. Since then, the Chinese government has stepped up efforts to bring Catholic churches into the official system and intensified its pressure on those that refuse to join.

China treats Buddhism – particularly Han Buddhism, the most widespread branch in the country – more leniently than Christianity or Islam. Xi frequently praises Han Buddhists for having integrated Confucian, Daoist and other traditional Chinese beliefs and practices.

At the same time, China has cracked down on Tibetan Buddhists. Recently, Chinese authorities have been accused of carrying out “political re-education” campaigns meant to cement allegiance to Xi and discourage loyalty to the exiled Dalai Lama. Moreover, the Chinese government has been criticized for tearing down Tibetan Buddhist monuments, including monasteries and statues.

Folk religion and ancient spiritual traditions play a large role in China. The government encourages some activities that it considers to be part of China’s cultural heritage and has financed the renovation of some folk religion temples. People in China are allowed to venerate the Chinese philosopher Confucius and participate in temple festivals where folk deities – e.g., Mazu, the goddess of the sea – are worshipped. Authorities have also brought Mazu festivals to Taiwanese worshipers as a way to gain political favor.

The Chinese government has tasked local governments with regulating folk religious activities to ensure they reflect cultural heritage and are guided by socialist values. Since 2015, local authorities have been registering temples with historical and cultural importance and making efforts to bring their staff and activity under state supervision. In some provinces, temples that local authorities perceived as socially and culturally insignificant have been demolished or closed, or converted into secular facilities.

Religious activity that falls outside of the five officially recognized religions and does not meet the government’s approval as a form of cultural heritage is often categorized by authorities as “superstition” or “evil cult.” For instance, Chinese law forbids witchcraft and sorcery, and the government opposes folk religious practices that include a superstitious element such as setting off firecrackers to ward off evil spirits.

Some groups, including Falun Gong, the Unification Church and the Children of God, are considered cults and banned. The government has been accused of arresting Falun Gong practitioners and subjecting them to systematic torture, such as organ harvesting.

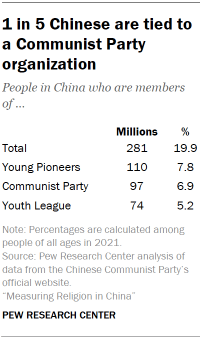

The ruling Chinese Communist Party promotes atheism and discourages citizens from practicing religion. The 281 million Chinese people who belong to the CCP or its affiliated youth organizations are officially banned from engaging in a broad range of spiritual activities.

Still, the CCP tolerates occasional engagement in cultural customs. For example, it is acceptable to visit temples every once in a while. But visiting temples for all important religious days or frequently consulting fortunetellers can lead to expulsion from the CCP. Nevertheless, some CCP members do identify with a religion or engage in religious practices, though generally at lower rates than non-CCP members.

Children under 18 are constitutionally prohibited from having any formal religious affiliation in China. There is also a ban on religious education, including Sunday schools, religious summer camps and other forms of youth religious groups. Schools focus on promoting non-religion and atheism, and many children join CCP-affiliated youth groups, where they must pledge commitment to atheism.

China’s attitude toward religion dates back to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Early CCP leaders denounced religion as linked to “foreign cultural imperialism,” “feudalism” and “superstition,” and persecuted religious groups across the board. During the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), CCP chairman Mao Zedong vowed to eliminate “old things, old ideas, old customs and old habits,” and Red Guards attacked or destroyed many temples, shrines, churches and mosques.