The first time I got punched in the face in a training session I cried afterwards in my car.

It wasn’t so much that it hurt: it was the shock. I froze, but I was encouraged to punch back. Boxing brought up buried emotion deep inside of me. As much as it didn’t seem very tough to shed tears, the process felt part of my healing journey.

I started boxing in my mid-thirties. I was angry and I knew it was directly related to my childhood sexual abuse and trauma. Secretly I felt drawn to boxing, its visceral nature. The prospect of hitting someone in the face and maybe even knocking them out excited me.

Little did I know that within a few months of signing up to a boxing gym, I would be training for my first fight. I went on an 18-month beginner’s journey into the world of master’s boxing, an amateur division for those aged 35 and older.

Ella Sowinska, Author provided

Fighting as a metaphor

My first fight was my most memorable. I fought a woman in her fifties who had a gold tooth. She was tough with a mean look in her eye and I loved every bit of the experience. The brilliance of naivety! It was a split decision, but the final point went to her. I lost, but I didn’t care. I felt elated. The feeling was short-lived, as I fought another three times and lost.

The more I took fighting into the competitive space, the more disempowered I became. Lack of experience was a key factor, but performance anxiety overtook me. I practised mindfulness (a difficult task for someone who had experienced dissociation her whole life). I tried to visualise winning and work with my inner children to quell the fear and voices, but to no avail. I dissociated in the ring.

As I lost fights, the chant of negative voices became louder within me. The unconscious beliefs I had – about being a failure, a loser and worthless – started to overtake me. I kept powering on, fighting hard to battle through the negativity. Fighting became a metaphor for recovering from my abuse.

Ella Sowinska, Author provided

The training motivated me; I trained five times a week. I started running to increase my cardio. I got a trainer and we spoke daily about my routine and mental health. I remember driving to a sparring session with him one day. He said, “You are the most difficult person I have ever trained.” I looked confused. He went on; “Most people when they get hit, punch straight back. When you get hit, you just freeze.”

I responded that it was instinctual. I would dissociate. Boxing triggered the feeling of the loss of control and anxiety associated with my past trauma. But I kept returning to it, determined to crack the code to release me from my bind and break through to the other side. Yet my trauma continued to undermine my boxing.

I struggled to think logically and stay calm, let alone be present. I loved how boxing challenged me to try to overcome these fears, but the self-criticism, judgement, disappointment and confusion connected to trying to win became harder to reconcile.

After my final loss, I ended up having a win, in a small interclub fight. The stakes weren’t as high as the other fights and I didn’t even know it was a win/lose fight. I took home a medal and it felt bittersweet. At least I could say I won one, I guess.

More than half of Australians will experience trauma, most before they turn 17. We need to talk about it

Boxing as a recovery tool

I loved being a fighter, even if I wasn’t very good at it. I have mostly been determined to fight my way through life and work through things, rather than running from them.

After a period of reflection, I knew that what I enjoyed about boxing hadn’t changed. Hitting a bag hard, training, sweating, focusing on my body and breath, movement and speed; toying with being relaxed and calm, yet sharp and on point. Boxing is a delicate interplay between the physical and the mental. It is both art and skill. It is these elements that have kept me coming back to this sport.

Although my fighting career was over, I began to wonder if there were other women like me; survivors, who could use boxing as a recovery tool, a mode of empowerment to express their trauma. I wanted to not only box with survivors – I wanted to hear their stories and share my experiences of trauma.

My background is as an educator, a filmmaker, and an arts practitioner, so the juxtaposition of writing and boxing, although contradictory, felt right to me. I wanted to know what would happen if you put a bunch of survivors in a gym to firstly write about their trauma and then learn the basics of boxing to channel the feelings.

And so, in 2018, I set up Left/Write//Hook, which I ran independently. In 2019, I became a level one boxing coach. In 2020, I took the project into the research space at University of Melbourne, where I lecture in producing for film and television.

Left/Write//Hook is not about becoming a writer, or a fighter. I believe survivors need to give their trauma expression. I believe survivors are already fighters.

I knew what it was like to fight through shame, negative thinking, addiction, toxic beliefs – and even for the will to want to survive and live life. I knew that other survivors felt the same. Journal writing had helped me in the past, but I found it hard to do.

I felt sleepy after I wrote, as though expressing the trauma and then just leaving it there on paper was only one part of the process. I needed to give the words emotion, the memories a purpose. I needed to move the trauma through my mind, then into and out of my body.

The Body Keeps the Score: how a bestselling book helps us understand trauma – but inflates the definition of it

A virus had been with us all along

In 2020, I spent two weeks with a group of survivors of childhood sexual abuse and trauma, sitting in a boxing gym writing about our experiences. After the first hour of writing, I taught them how to box and get angry with the boxing bag.

The workshops were meant to go for eight weeks, but by the end of the second week, Covid pushed everyone online. Little did I know we would be spending most of that year together writing and boxing in our bedrooms and lounge rooms.

Ella Sowinska, Author provided

While the threat of the virus had reduced our capacity to physically interact, we reflected that a virus had been there with us all along. Inside our homes, in our nightmares, underneath our sheet covers, disintegrating our relationships – with our bodies and minds.

We wrote to prompts, designed to connect us to our trauma and provide context and perhaps relief to our shared experiences. Many of us had never spoken about our trauma beyond our therapist’s office.

‘Lit therapy’ in the classroom: writing about trauma can be valuable, if done right

Breaking the silence

I set up the workshop to break the silence of sexual abuse that I had been carrying since I was little. By the end of 2020, we had written an incredible body of work and decided to co-curate an anthology. Our writings had begun to offer an insight into the narratives we told ourselves, the lies that we believed – gently offering an alternative narrative, in the hope that it would one day become thicker.

When we heard each other’s stories of shame, disgust, fear and self-loathing, we related and felt empathy. We didn’t see each other the way we described ourselves. We saw each other as tough and brave, fierce and beautiful. And if we saw each other that way, then maybe we could learn to see ourselves in the same way.

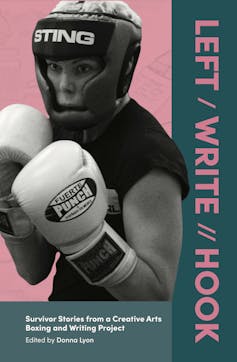

Left Write Hook: Survivor Stories from a Creative Arts Boxing and Writing Project collects our writings over three rounds of workshops held in 2020. It tells a story of a group of women and gender-diverse adults who are profoundly grappling with the long-term effects of childhood sexual abuse and trauma. They tell the story of friendship, belonging, connection, disconnection – but most importantly, of solidarity.

During the process of creating Left/Write//Hook (and related projects, including research, that have grown from it), each survivor has been given as much personal agency as possible at each moment. Some of us have gone on to publish journal articles together. We are making a documentary film about the project and we just launched this book together.

This agency ensures the survivor’s voice is always amplified. We are not subjects to be researched on or about – rather, with and by. We are experts of our own narratives, and in reclaiming and reauthoring our lives.

This article is excerpted and extended from the book Left/Write//Hook: Survivor Stories from a Creative Arts Boxing and Writing Project, edited by Donna Lyon.