Who funds Australia’s political parties? Besides the occasional scandal – think Aldi bags full of cash – most Australians would not hear much about it.

But money matters: political donations can buy access to politicians and create opportunities to sway public decisions in the donor’s favour.

New data, released today by the Australian Electoral Commission, provide the best information available on political party funding and Australia’s major donors. So let’s follow the money.

Big money was spent on the 2022 election – but the party with the deepest pockets didn’t win

Even in a non-election year, fundraising continued apace

In the 2022-23 financial year, Australia’s political parties collectively raised $394 million, with most of the money (88%) flowing to the major parties.

But in a rare turn of events, Labor raised substantially more ($220 million) than the Coalition ($125 million). The Coalition has been ahead on fundraising for more than a decade, but the gap closed in 2022 when Labor returned to power, and now Labor is in its strongest fundraising position on record.

Who are the major donors?

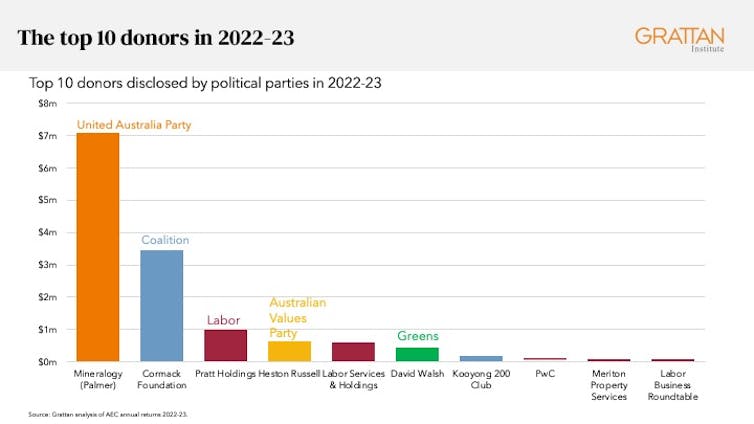

A few big donors dominate the $16.6 million in donations to political parties that are on the public record.

The single largest donor to Labor was Anthony Pratt, the paper and packaging businessman, who gave $1 million. This continues Pratt’s long history of big donations to both major parties, totalling more than $11 million over the past ten years.

Other major donors to Labor were Labor Services & Holdings ($598,000) – an investment vehicle for the party – and Labor Business Roundtable ($100,000), which runs fundraising events for the party.

The Coalition’s biggest donors were the Cormack Foundation ($3.46 million) – an investment vehicle for the party – and fundraising body the Kooyong 200 Club ($193,000). The Coalition also received $100,000 from Meriton Property Services, $90,000 from Laneway Assets, and $80,000 from John McEwen House.

But some of the largest single donations were to minor parties. Former MP Clive Palmer’s mining company Mineralogy gave $7 million to the party he founded, the United Australia Party. And Heston Russell, a former member of the defence force, gave $650,000 to the now-disbanded Australian Values Party that he founded.

Federal politics is awash in dark money

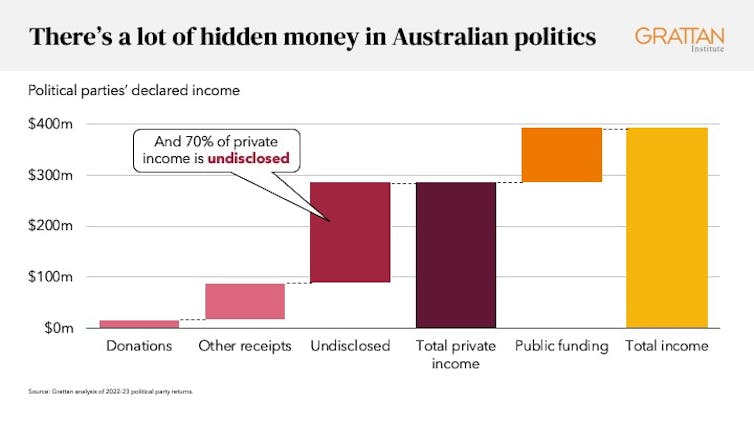

These are the big donors on the record, but declared donations make up only 4% of political parties’ total income. There are other sources of income on the public record, including public funding, but about half the money remains hidden.

Labor’s funding is particularly murky: 72% of Labor party income in 2022-23 was hidden, compared with 22% for the Coalition.

In the main, this isn’t because pollies are walking away with briefcases full of cash from shadowy carpark rendezvous. Giant holes in disclosure laws create plenty of perfectly legal dark corners.

At the federal level, parties were not obliged to disclose donations below $15,200 in 2022-23. This means, hypothetically, a donor could have donated $15,000 every week, adding up to $780,000 over the year, and political parties would not be required to declare it. The donor themselves has an obligation to tally their own donations and declare themselves when they reach the threshold, but there is no effective way to police this.

Even among the declared funds, it can be difficult to distinguish investment income from political fundraising, because income from fundraising events is not classified as a “donation” – it is instead grouped in with everything else in an ambiguous category of “other receipts”.

Are donations swaying decisions?

Some groups only donate – or donate much more – when particular policy issues are “live”.

Gambling was one of the top issues in the 2023 NSW state election, with the Liberal Party proposing tighter regulation of pokies. Gambling groups have a history of making big political donations when gambling restrictions are on the table.

Donations from gambling groups to NSW election campaigns are banned, but industry players still made their presence felt nationally. The ALP received $197,000 in income from pokies supporters (including Clubs NSW, Clubs Australia, and the federal and NSW branches of the Australian Hotels Association), while the Coalition received $123,000.

And accounting firm PwC – whose unethical behaviour in managing conflicts of interest in work for the public service came to the fore last year – continued its regular pattern of political donations and other party support, giving $422,000.

Explicit quid pro quo is probably rare, but there is still substantial risk in more subtle influences – that donors get more access to policymakers and their views are given more weight. These risks are exacerbated by a lack of transparency in dealings between policymakers and special interests.

The states show us a better way

Many of the states have stronger rules on money in politics than the Commonwealth.

For example, NSW and Victoria require election donations to be reported within 21 days, and cap total donations. They have lower thresholds for when donations must be made public, and have banned donation-splitting, so it’s harder to flout the threshold. And NSW sets limits on election spending, taking away the drive for politicians to fundraise quite so frenetically.

The effect of these rules is clear. Donations in the lead-up to the last federal election were dominated by a handful of people and organisations: 5% of donors contributed 73% of declared donations. In contrast, in the most recent NSW and Victorian elections, the top 5% of donors contributed just a third of donations. Better rules help to reduce the potential influence of individual donors.

Federal parliament just weakened political donations laws while you weren’t watching

Federal donations reform is on the horizon

The federal donations disclosure regime has long lagged the states. But there are finally signs of change afoot.

A federal parliamentary committee inquiry into the 2022 election has recommended several changes to better regulate money in Australian politics, including:

lowering the donations disclosure threshold to $1,000 to reduce the amount of dark money in the system

introducing “real time” disclosure requirements so that Australians know who’s donating while policy issues – and elections – are still “live”

introducing expenditure caps for federal elections to reduce the fundraising arms race.

It is still to be seen if the government will implement these recommendations. It should, because better rules around donations would ensure Australians know who funds our political parties and enable us to keep our politicians in check.