It’s Sunday and your family are sat around the dinner table. There’s a bird roast, gravy and then there’s your vegan brother Tom. Your mum’s upset that he will not try a bit of the gravy on his vegetables and Grandpa is surprised that chicken even counts as meat.

We can be certain that the dinner conversation will soon circle around to how “normal, nice, necessary and natural” meat eating is. These are the four main rationalisation strategies that omnivores use to defend their dietary choices.

A vegan’s intentions are good. Most of them avoid using animal products because they don’t want to cause animals harm. But this can put your relationships under strain. When people first go vegan, “eating with others” is one of the main reasons it ends up not working out.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our twenties and thirties. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

Long COVID: a range of diets are said to help manage symptoms – here’s what the evidence tells us

How running can help you cope with stress at work

Hope from despair: how young people are taking action to make things better

But a new type of meat-reducer is emerging: the “social omnivore”. This growing trend refers to people who will go for a kebab with their friends but will not eat meat when at home or on their own. It’s hard to say how common the phenomenon is, but the mantra is to avoid eating meat where you can and avoid social conflict when eating out.

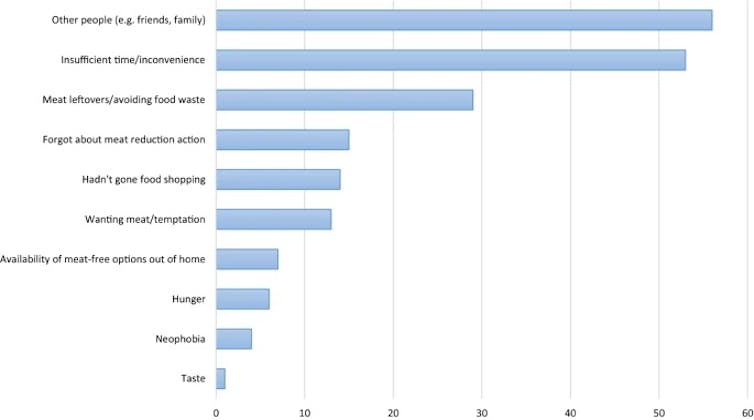

Barriers to eating less meat:

Frie et al (2022), CC BY-NC-ND

Why don’t you eat meat?

There are many reasons to avoid eating meat. No other food releases more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere or causes more habitat destruction than meat. Red meat in particular is also associated with an increased risk of heart disease, certain cancers and suffering a stroke.

Then there’s the uncomfortable truth that sentient animals have to die in order for us to eat meat.

What kind of meat-avoiding diet is right for you will depend on your underlying motivations. If you see meat as murder, then you will have to go all the way and follow a vegan diet. Around 2%–3% of people in Britain currently declare themselves to be vegan.

If you feel that consuming dairy is okay, becoming vegetarian may be a better option. The vegetarian population stands at 5%–7% of British people.

Nuntiya/Shutterstock

But if your dietary choices are driven by concerns for your health or the environment, an occasional meaty treat should not make you question your identity. Research from 2012 found that even by eating half as much meat and dairy, we could cut greenhouse gas emissions by 19% and prevent almost 37,000 deaths each year in the UK.

If this diet reflects you, then you can join the 13% of Brits who eat meat only occasionally – called “flexitarians”.

A social omnivore is a kind of flexitarian with a very clear rule about when they will eat meat: when it is served in a social setting. This can be much more effective than a general flexitarian intention to eat “less meat”. In this case, how much less meat or when to have it are decided on a moment-to-moment basis.

Clear rules

Research shows that a gap exists between our good intentions and behaviour. Whether it’s exercising more or eating fewer calories, we all tend to suffer from optimistic bias. This is the mistaken belief that we are closer to our goal than we really are.

If your intentions are not underpinned by clear rules, this gap can quickly become a gulf. We have to make many decisions about what to eat every day, and often under time pressure. If there are no clear rules to follow, we may fall into old habits rather than follow our good intentions.

Setting rules can help change behaviour because they reduce the cognitive load of multiple decisions every day. At the University of Oxford, we tested whether an online programme, called Optimise, could help prospective flexitarians reduce their meat consumption more effectively.

The programme involves completing a questionnaire to establish how much meat you currently eat before choosing from a range of different strategies each day for nine weeks to reduce your meat intake.

These might include suggestions like: “avoid the meat and fish aisle when shopping” or “go to a vegetarian or plant-based restaurant”. At the end of the programme, you will have a set of meat-reducing strategies, or rules, to put your low meat-eating intentions into practice.

In 2020, we trialled the programme on 151 meat eaters. After five weeks, the programme led to a 40g per day reduction in meat intake. This equates to between one and two fewer rashers of bacon each day.

Blue Titan/Shutterstock

Is it going to make a difference?

Given the largely linear association between meat intake and harm to health and the planet, any reduction in the amount of meat you consume is likely to be beneficial.

A report from the EAT-Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, Health (a global group of scientists who define targets for healthy diets and sustainable food production) suggests that a diet that is both healthy and sustainable should contain no more than 98g of red meat, 203g of poultry and 196g of fish per week. That’s plenty for an occasional feast with friends.

Big journeys begin with small steps. Becoming a social omnivore today will be better for your health and the environment than a plan to become a vegan tomorrow.