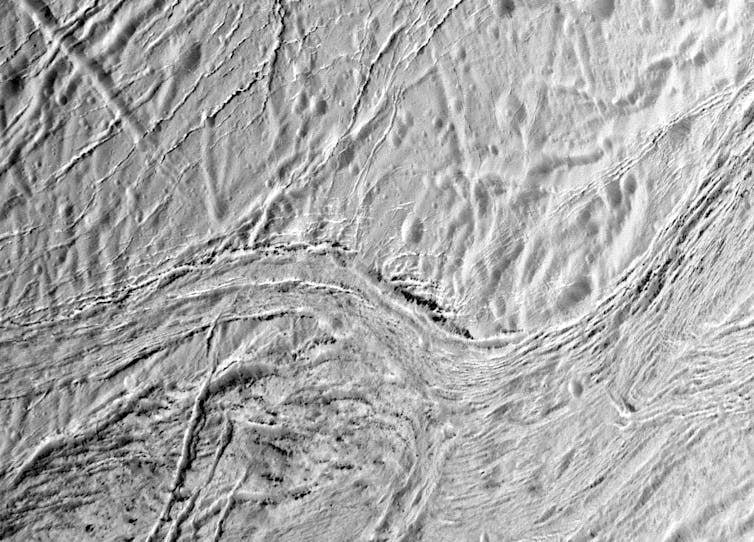

Enceladus is the tiny moon of Saturn that seems to have it all. Its icy surface is intricately carved by ongoing geological processes. Its icy shell overlies an internal, liquid ocean. There, chemically charged warm water seeps out of the rocky core onto the ocean floor – potentially providing nourishment for microbial life.

Now, a new study, published in Nature, has uncovered more evidence. It presents the first proof that Enceladus’s ocean contains phosphorous, an element that is essential to life.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

The Cassini spacecraft, operated in orbit about Saturn 2004-17 by Nasa and the European Space Agency (Esa), found plumes of ice particles venting from cracks. These penetrate right through the icy shell so that the ocean water at the bottom of each crack is exposed to the vacuum of space, where the lack of confining pressure causes it to bubble and vaporise in the form of plumes.

These plumes provided samples of spray from Enceladus’s internal ocean that were scooped up for analysis by Cassini during several close fly-bys – a bonus that wasn’t anticipated when the mission was initially planned.

Particles analysed during these brief passages through the plumes demonstrated that the ice is contaminated by traces of simple organic molecules as well as molecular hydrogen and tiny particles of silica. Taken together, these indicate that chemical reactions between water and warm rock take place on the ocean floor, most probably at “hydrothermal vents” (a fissure releasing heated water) similar to those on Earth.

This is significant. It means Enceladus has all the ingredients for microbial life to sustain itself (in the absence of sunlight). It is in fact the setting considered most likely to have helped life on Earth begin. If it happened on Earth it could have happened inside Enceladus too.

Missing link

All life on Earth requires six essential elements: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorous and sulphur – known collectively by the scarcely pronounceable acronym CHNOPS. Five of these six essential elements were detected in Enceladus plume samples several years ago, but phosphorous had never been found.

Phosphorous is a vital ingredient, because it is needed for the phosphate groups (phosphorous plus oxygen) that link the long chains of nucleic acids such as DNA and RNA that store genetic information. It also allows cells to store energy by means of molecules such as adenoside triphosphate (ATP for short).

Of course, we don’t know for sure that life inside Enceladus (if it exists) is obliged to use nucleic acids or ATP. However, because the presence of phosphorous is essential for life as we know it, it makes Enceladus a more likely prospect now that we are certain that there is enough phosphorous available there.

NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Canny collecting

The team found Enceladus’s phosphorous by avoiding the cluttered data collected during the Cassini’s frantically quick zooms through the plumes. Instead, they scoured sparser data accumulated in a more leisurely fashion by Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer during 15 periods between 2004 and 2008 while Cassini was travelling within one of Saturn’s rings: the “E-ring”. Enceladus travels along this hoop as it orbits.

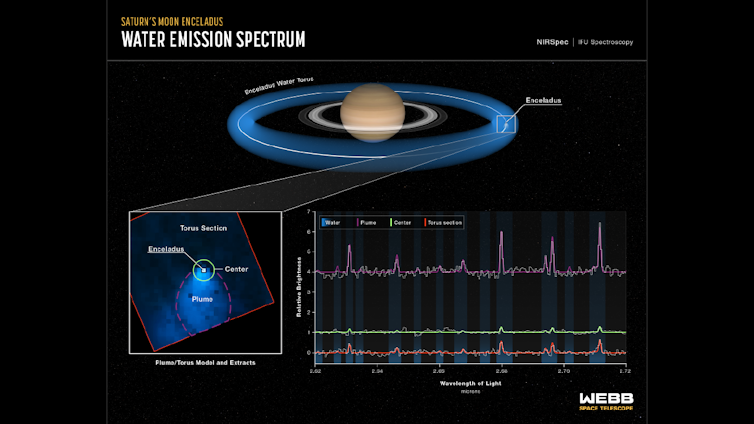

The E-ring hoop is more than 2,000km thick. About 30% of the ice particles emitted in Enceladus’ plumes end up there, as demonstrated by a recent image from the James Webb Space Telescope, which is the only proof we have that the plumes were still active five years after the end of the Cassini mission.

NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Leah Hustak (STScI)

Sorting through analyses of nearly a thousand ice particles, which are believed to represent frozen spray from Enceladus, the researchers found nine of them that contained phosphates. This may sound like a slim haul, but it is enough to demonstrate that Enceladus has more than enough dissolved phosphorous in its ocean to permit the functioning of life there.

Indeed, follow-up laboratory experiments suggest that the concentration of dissolved phosphorous in Enceladus’s ocean water may even be hundreds of times greater than in Earth’s oceans.

The team argue that their findings and associated modelling make it likely that any icy moon that grew further from the Sun than the Solar System’s “carbon dioxide snowline” – a location where temperatures during planetary formation were low enough for carbon dioxide to become ice – is likely to contain abundant phosphorous. This condition is met for icy moons at Saturn and beyond, but not at Jupiter.

Jupiter’s distance from the Sun places it beyond the “water-ice snowline” (where water becomes ice), but it is too close to the Sun, and hence too warm, to be beyond the carbon dioxide snowline.

So where does this leave Jupiter’s moon Europa, a target for missions due to arrive about ten years from now?

This moon has been widely touted as potentially able to support a more flourishing biosphere than Enceladus because of its larger size and greater store of chemical energy in its rocky interior. The team behind the new study are reticent on this, but their modelling suggests a phosphate concentration in Europa’s internal ocean about a thousand times less than at Enceladus.

To me, that is not a gamechanger, and we should continue to expect Europa to be habitable. But it would be reassuring to find some proof of phosphorous there too.

The chemistry that could feed life within Saturn’s moon Enceladus: study gives clue ahead of flyby