When Canada legalized cannabis in October 2018, there were many concerns about its potential impacts. One of them involved cannabis-impaired driving.

Before legalization, police were already catching more drug-impaired drivers each year. So, people naturally worried that more stoned drivers would appear on the road after legalization.

To lower that risk, the federal government updated its driving laws. Impairment by alcohol or drugs separately was already illegal. In December 2018, Canada also banned impairment by combinations of alcohol and drugs, or by unspecified substances.

Cannabis-impaired driving: Here’s what we know about the risks of weed behind the wheel

The government likewise helped police to better enforce those laws. For example, it gave them more power to obtain breath and blood samples from drivers. And it funded more training to help them recognize symptoms of drug impairment.

However, it was unclear how much impaired driving would really increase due to legalizing cannabis.

For example, drivers injured in collisions often test positive for cannabis, but also for other drugs. Cannabis consumers claim they are driving less often after use. And police say that drivers’ symptoms more often imply impairment by stimulants or narcotics than by cannabis.

Given this uncertainty, I decided to dig into the police data.

Police-reported impairment

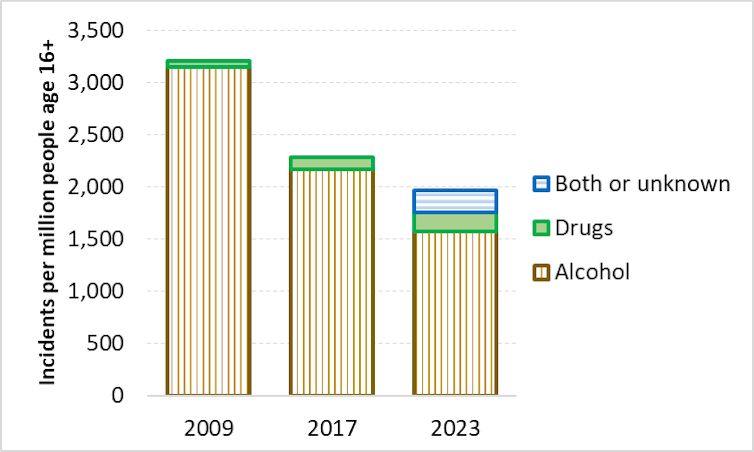

My research analyzed the annual rates of impaired driving cases that police investigated between 2009 and 2023. The reporting covered four substance categories: alcohol, drugs, drugs-and-alcohol combined and unknown substances.

Note that “drugs” includes cannabis but also other chemicals like opioids and amphetamines. Publicly available data unfortunately don’t name the drugs involved.

I first estimated the trends in alcohol and drug impairment up until 2018. I then calculated how much rates changed from 2019 onward.

I also checked several potential explanations for those changes. Those included the level of legalized cannabis sales and the share of adults consuming cannabis in each province. I also considered each province’s number of police trained in drug recognition and their degree of COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

The data showed that during the 15-year study period, alcohol remained the most common impairment category. But its share of all cases dropped from 98 per cent in 2009 to 95 per cent in 2017 and to just 80 per cent in 2023.

Up until 2018, the total impairment rate also fell each year.

Statistics Canada, CC BY

More drinks and drugs

But in 2019, rates jumped substantially. As a result, police reported 31 per cent more impairment cases during 2019-23 than the 2009-18 trend had projected.

The impairment increases varied between provinces. For example, there was no significant change in Québec and Saskatchewan. But rates doubled in British Columbia and Newfoundland.

Percentage-wise, the drugs category saw the most growth. It averaged 42 per cent higher during 2019-23 than had been projected.

But alcohol impairment rose too. It averaged 17 per cent above its previous trend.

And when counting drivers, alcohol’s growth was larger. The increase in drinking drivers caught by police was four times the increase in drugged drivers.

The new offenses for impairment by drugs and alcohol combined, or by unspecified substances, also contributed to the higher rate.

So, police clearly found more impaired drivers after 2018. But was that because more impaired drivers were on the road? Because police got better at catching them? Or both?

Statistics Canada, CC BY

Constables, COVID and cannabis

My analysis showed the impairment changes were correlated most strongly with the number of police trained in drug recognition. Not surprisingly, when provinces gave police more training, they caught more impaired drivers.

The restrictions that provinces imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic showed the second biggest correlations with impairment. But interestingly, alcohol and drugs diverged: when provinces tightened restrictions, they got less impairment from alcohol but more from drugs.

Presumably, lockdowns meant fewer bars open, and so fewer people driving home drunk. But perhaps lockdowns also meant more laid-off workers using drugs at home before going grocery shopping.

Alcohol sales changed subtly after Canada legalized cannabis

Alcohol impairment showed no relationship with the numbers of Canadians consuming cannabis or the amount of cannabis legally sold. That’s not surprising. Canadians didn’t suddenly replace their cabernet with cannabis after legalization.

But it was surprising that drug impairment likewise showed no relationship with cannabis consumer numbers. And it was only weakly correlated with legal sales.

This might imply that most drug impairment came from chemicals other than cannabis. Or perhaps most legal cannabis purchases simply replaced existing illegal ones, rather than adding to total usage.

Consuming responsibly

Overall, Canadian police reported noticeably more drug-impaired and alcohol-impaired driving after 2018. But the growth seemed related mostly to enhanced enforcement and pandemic disruptions, rather than to legalized cannabis. And fortunately, the long-term decline in impaired driving resumed in 2020.

All road users benefit from that continuing decline. And we each play a role in maintaining it. Whether your preferred intoxicant is booze, weed or something else, please consume responsibly. And use designated drivers or public transit to get home.

After all, flashing coloured lights look much nicer on a tree standing in your home than on a police car pulling you over.