Bad Sex – like Bad Feminist (the title of the essay collection that launched Roxane Gay to literary stardom back in 2014) – is an enticing title for a book. Who hasn’t had bad sex at some time or other, including those of us who identify as feminists?

Bad sex, variously defined and experienced, continues to be depressingly common, even though sex “has never been more normalised, feminism has never been more popular” and “romantic love has never been more malleable”.

Or, so argues Nona Willis Aronowitz, in her genre-defying first book, Bad Sex: Truth, Pleasure and the Unfinished Revolution.

Bad Sex: Truth, Pleasure and an Unfinished Revolution – Nona Willis Aronowitz (Plume).

Aronowitz’s regular writing gigs include a love and sex advice column for Teen Vogue. But in taking “bad sex” as her subject, she’s less concerned with offering remedies than in the “broader question of what cultural forces interfere with our pleasure, desire and relationship satisfaction”.

What has changed, what remains

In her cleverly constructed investigation, Aronowitz makes this a personal and historical question, as well as a feminist dilemma. Across 11 chapters, she blends memoir, social history, feminist analysis and cultural commentary in a highly readable, often insightful – and occasionally self-indulgent – fashion.

Hers is a very US-centric story: the backdrop to her investigations is the election of Donald Trump and his term in office, which heightened the chaos of her personal world, and her feminist framework is almost exclusively US-based. But Bad Sex has wider resonance and appeal.

The starting point is Aronowitz’s own compulsion to understand and move beyond the “bad sex” that eroded her otherwise satisfying (though ultimately short-lived) marriage. Through her “zig zag pursuit of sexual liberation”, Aronowitz ranges across the contemporary sexual landscape – dating apps, ethical non-monogamy, sexual and gender fluidity – while also looking back to feminist and gender history to contemplate what has changed, and what perennials remain.

These include the murky edges of consent (a conversation, she reminds us, that started well before #MeToo), everyday forms of sexual coercion, and the “woke misogynist” – a contemporary type with antecedents like “men’s libbers”.

Yet despite what the title might suggest, sexual harm is not her main concern and Bad Sex is not a #MeToo book. Aronowitz wants to bring both pleasure and nuance back to the centre of feminist sexual politics, including by way of telling the truth about how difficult it can be for women to pursue (or even identify) their desires in an enduringly patriarchal world.

Sometimes this involves poking gentle fun at herself and the whole concept of “feminist sex”. (“I wanted my hook-ups to be both fulfilling and morally sound”.) But there’s no doubting her commitment to the task – which includes knowing her history.

Mike Nelson/EPA

Feminist sexual revolutions and sex wars

The “unfinished revolution” of the subtitle is the explicitly feminist sexual revolution launched by women’s liberationists like Anne Koedt, whose essay The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm was first published in 1968.

By harking back to it, Aronowitz offers an updated telling of the heady and horny history of early radical feminism – as captured in Jane Gerhard’s Desiring Revolution: Second-Wave Feminism and the Rewriting of Twentieth-Century American Thought, 1920 to 1982 (2001), and before that, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America 1967-1975 (1989) by Alice Echols.

In this century, “radical feminism” has ossified into a catch-all for what many see as the most negative and obstinate manifestations of feminism – among them transphobia, anti-porn and anti-sex work, gender essentialism, and an agenda dominated by white, middle-class women.

But Gerhard and Echols, among many others, have recuperated a vibrant and multi-faceted lineage of radical feminism in which good sex was integral to liberatory feminist politics.

The points at which those earlier histories conclude are significant. Echols stops in 1975. She says that’s when “cultural feminism” became the dominant strain of feminism in the US, marked by separatism and a female counterculture that alienated many heterosexual and bisexual women – not to mention lesbians who were turned off by what they saw as the policing of their sexual desires.

Gerhard continues to 1982, the year of the historic Scholar and the Feminist Conference at Barnard College. Entitled “Towards a Politics of Sexuality”, the conference was convened by feminists eager to return to (and extend) feminism’s earlier focus on sexual pleasure – much to the consternation of anti-porn feminists. They protested outside, wearing T-shirts with “For a Feminist Sexuality” on one side, and “Against S/M” on the other.

The Barnard Conference did not launch the “Feminist Sex Wars” – with “pro-sex” feminists on one side and the so-called “anti-sex” feminists on the other. It certainly galvanised them, though. And it has been heavily dissected and narrated ever since, including by those who were there.

Anthropologist Gayle S. Rubin, part of the West Coast lesbian sadomasochism scene, was still a graduate student when she presented an early version of her since much-anthologised essay, “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality”, at the conference.

In her essay, Rubin lamented the “temporary hegemony” of the anti-pornography movement, defended pro-sex feminism as part of a longer tradition of sex radicalism, and provocatively challenged the “assumption that feminism is or should be the privileged site of a theory of sexuality”. This last point partly accounts for why Rubin’s essay is as canonical to queer theory as it is to feminist thought.

In a lecture delivered earlier this year, Rubin noted a resurgence of interest in the Feminist Sex Wars, post-#MeToo. It’s evident in a surge of books released in 2021. There were two dedicated revisionist histories: Lorna Bracewell’s Why We Lost the Sex Wars: Sexual Freedom in the #MeToo Era and Brenda Croswell’s The New Sex Wars: Sexual Harm in the #MeToo Era.

And those Feminist Sex Wars were part of philosopher Amia Srinivisan’s lauded essay collection The Right to Sex. Srinivisan also wrote an essay for The New Yorker on the Sex Wars, extending its preoccupations to the British context.

Each of these books is markedly different in its emphasis. Bracewell spotlights the participation of queer women of colour. Croswell contemplates the limits of the law for addressing sexual assault. And Srinivisan re-evaluates anti-porn feminism in light of contemporary concerns. All three, however – like Aronowitz – see the feminist politics of sex as unfinished business, with the Feminist Sex Wars of the 1980s offering both guidance and a cautionary tale.

For Rubin, however, the new literature on the Sex Wars – some of it tainted with errors of fact – is not so much history as a reiteration of myths and recycled narratives. These books reflect what she sees as a “growing tendency to pontificate on these earlier conflicts without actually knowing what was going on in them”, nor the context in which they unfolded (notably – the Reagan administration, the rise of the Christian right and the onset of the AIDS crisis).

Rubin recalls the Sex Wars as traumatic for many reasons, including because they eclipsed an earlier, more wide-ranging and libidinous feminist sexual agenda. Early radical feminists and women’s liberationists, says Rubin, were “incredibly concerned with sex, sexuality, women’s sexual pleasure, along with violence, rape and battery, and a whole lot of other things”.

One of the most prominent was Ellen Willis, author of “Towards a Feminist Sexual Revolution” (published in 1982), among other key essays. Two years later, her daughter (with activist and scholar Stanley Aronowitz) was born: Nona Willis Aronowitz.

Is the #MeToo era a reckoning, a revolution, or something else?

Like mother, like daughter?

Like many millennial women, Aronowitz came of age with “pro-sex” feminism on the ascent. But though she was literally raised by one of the recognised progenitors of that feminism, she says while she was growing up, her mother “didn’t pry or even offer” counsel on puberty or sex.

Willis died in 2006, when Aronowitz was in her early 20s. It’s primarily through her mother’s writings that she’s absorbed her views on sex and relationships, including as editor of the posthumous collection The Essential Ellen Willis (2014).

Minnesota University Press, CC BY

In Bad Sex she digs deeper, reading through her mother’s letters and personal papers to piece together her sexual experiences and past relationships – including with Aronowitz’s father. Some of what she finds is confronting (especially about her dad’s first marriage). But there’s also solace, wisdom and solidarity to be found in her mother’s life and writing, and those of others like her, who have made (or continue to make) “good sex” central to their feminism.

Willis began her writing career as a rock critic. She was initially wary of the version of women’s liberation she found in Notes from the First Year (1968), a collection of writings from New York radical women.

“Sexuality,” writes Aronowitz, “was all over Notes” – including Koedt’s advocacy for the clitoris and call to “redefine our sexuality”, and Shulamith Firestone’s transcription of one of the group’s meetings on sex, a somewhat damning indictment of the sexual revolution.

Willis wrote at the time that “the tone strikes me as frighteningly bitter” – but within months of meeting the New York women, she was a total convert. She formed the breakaway group Redstockings with Firestone, who went on to write the feminist classic The Dialectic of Sex (1970). Willis also re-evaluated her relationship with her boyfriend in the light of what consciousness-raising had exposed, and went on to spend much of her thirties single.

By the end of the 1970s, Willis was an eloquent critic of the then-emerging anti-pornography feminism. She warned in a landmark 1979 essay that if

feminists define pornography, per se, as the enemy, the result will be to make a lot of women afraid of their sexual feelings and afraid to be honest about them.

In the same essay, Willis shared that “over the years I’ve enjoyed various pieces of pornography […] and so have most women I know”. A couple of years later, in “Lust Horizons: Is the Women’s Movement Pro-Sex?” (1981), Willis surveyed the flashpoints.

She concluded that both “self-proclaimed arbiters of feminist morals” and “sexual libertarians who often evade honest discussion by refusing to make judgements at all” were obstacles to “a feminist understanding of sex”. By her lights, that involved recognising that “our sexual desires are never just arbitrary tastes”.

Shulamith Firestone: why the radical feminist who wanted to abolish pregnancy remains relevant

A candid narrator

Aronowitz is clearly indebted to her mother’s style of feminism. Her description of Willis’s particular niche (in the introduction to The Essential Ellen Willis) could well describe her own. She was intellectual, but not academic. She was a journalist, but not primarily an “objective” reporter; she “poached from her life and detailed her thought processes”.

Like her mother, Aronowitz is alert to the grey areas between utopian feminist visions of sexual liberation and the tricky realities of heterosexuality – or in Aronowitz’s case, heteroflexibility. “Reconciling personal desire with political conviction,” she writes, “is frankly, a tall order,” but nevertheless “essential”.

Yet while Willis stopped short of memoir, Aronowitz – reared on social media as much as feminism – is a candid narrator. It’s hard not to bristle with sympathy for her now ex-husband Aaron when she describes their sex towards the end as “metastasizing in the worst way”, or her own experience of it as “some putrid combination of bored, irritable, and disassociated”.

Elsewhere, Aronowitz describes her sexual encounters when her marriage is opened up, while she’s separated and as she moves into a new relationship – in enough detail to possibly tip over into too-much-information territory for some readers.

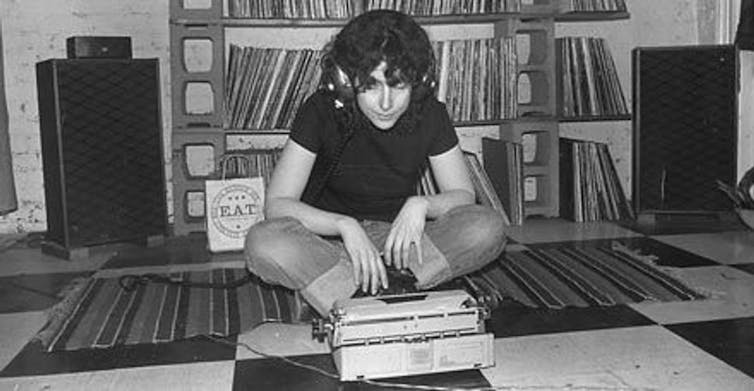

Photo by Emily Shechtman

What stops Bad Sex from descending into an extended confessional is that her truth-telling (which is different to tell-all) is not a solipsistic exercise. Aronowitz knows the limits of extrapolating from one’s own experience – especially if, like her, you’re a white, middle-class feminist with a big platform – and that the best way to do it is to be honest and to share the stage.

She reveals she enjoyed the social capital accrued from getting married and was terrified of being thirtysomething and single. And how she violated the rules of ethical non-monogamy (crossing over into a far less progressive “affair”), and largely went through the motions of queer experimentation.

Aronowitz indicts herself as much as she does her own generation of so-proclaimed sexual renegades. But hers is not a satirical gaze; her quest to understand what makes sex “good” or “bad” – and why it matters – is genuine.

Aronowitz typically launches each chapter with a personal experience: either her own, or from someone who offers a different perspective. Like her friend Lulu, a Black, queer woman, whose personal and family histories preface a larger discussion of the distinctive trajectories of black feminist sexual thought.

Readers with prior knowledge will be familiar with some of the key works and figures Aronowitz showcases (for instance, Audre Lorde’s classic 1978 essay “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power”). She weaves these classics together with contemporary literature and activism (like adrienne moore browne’s 2019 book Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good). And so, she provides entry points for different potential audiences: readers seeking a historical primer, and readers who are after an update.

The gap between theory and practice – or the challenge of what Sara Ahmed calls living a feminist life – is of special interest to Aronowitz. She manages to both capture the power of polemic in feminist history and to get behind the scenes.

For instance, Aronowitz reminds us, even Emma Goldman, the defiant anarchist who inspired women’s liberationists with her proclamations of free love, was hardly immune to romantic despair.

Elsewhere, she revisits essays by radical feminists Dana Densmore and Roxanne Dunbar on celibacy and asexuality as essential and invigorating aspects of second-wave feminist sexual thought.

When Densmore later tells her there wasn’t anyone in their militant group, Cell 16, who was actually celibate, Aronowitz isn’t surprised or judgemental. Instead, she heeds what Densmore saw as the most important sentence of her essay – one Aronowitz had originally overlooked:

This is not a call for celibacy but for an acceptance of celibacy as an honourable alternative, one preferable to the degradation of most male-female sexual relationships.

Sex, Densmore tells her, was “really bad in 1968”. In the early phase of the sexual revolution, when feminism had yet to happen, “it felt important to tell women they could walk away from bad relationships.”

Friday essay: ‘with men I feel like a very sharp, glittering blade’ – when 5 liberated women spoke the truth

What now?

Over 50 years later, Aronowitz has a lot to share with readers about sex. But her book is no polemic. In thinking about sex – her own and in general – feminism has clearly been an enormous and generative influence, but Aronowitz also acknowledges its limits and shares her frustrations. “I felt grateful”, she writes, “for the radical feminism that encouraged shame-free sexual exploration but I resented its high bar too.”

Crucially, however, Aronowitz does not disavow feminism or make grand claims about what sex should or should not be. That phase, Aronowitz suggests, was necessary once, but is now over.

This sets Bad Sex productively apart from other recent books, such as Louise Perry’s The Case Against the Sexual Revolution: A New Guide to Sex in the 21st Century (2022). Perry’s somewhat unrelenting diatribe against sex-positive feminism concludes with motherly advice to her readers, including “don’t use dating apps” and “only have sex with a man if you think he would make a good father to your children”.

For Aronowitz, ultimately the “unsteady conclusions of liberationists” – including those of her mother – were more inspirational “than any righteous slogan”. Bad Sex offers a rich compendium of these teachings, but its value is more elusive and greater than this.

In sharing her doubts, reflections and vulnerabilities, Aronowitz pushes feminist sexual politics beyond the binaries it is sometimes reduced to: pleasure/danger, positive/negative, pro/anti. Instead, she pushes it towards the complex engagement that Ellen Willis, among others, had encouraged all along.