David Baker’s Sex: Two Billion Years of Procreation and Recreation condenses the story of the evolution of (predominantly) reproductive sex into 300 pages. That is quite a feat.

The book is one of the latest additions to the popular “Big History” genre. First defined by Macquarie University historian David Christian in the early 1990s, the idea of Big History is that the temporal scale on which history should be studied is “the whole of time”. Its ambition is no less than to survey history from the Big Bang to the present, taking an interdisciplinary approach to its scholarship.

Baker is a science writer with a PhD in Big History and one of the writers behind the Big History Crash Course on YouTube. In his introduction to Sex, he declares “this is the first book that seeks to weave together the grand narrative of sex in its entirety”.

Sex: Two Billion Years of Procreation and Recreation – David Christian (Black Inc.)

The book is divided into three sections. The first – titled Evolutionary Foreplay – covers the period from 13.8 billion to 66 million years ago. Baker races through the 10 billion years following the Big Bang, when “the cosmos was devoid of life”.

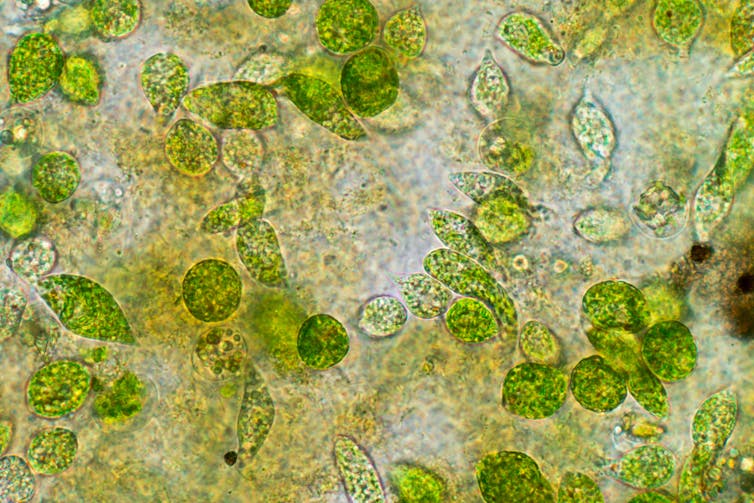

He summarises the formation of Earth and its atmosphere, the origins of living organisms 3.8 billion years ago, the emergence of DNA, and the cloning (asexual reproduction) of “microscopic blobs living on the edge of underwater volcanoes”.

We are taken from the earliest forms of sexual reproduction between two single-celled organisms to the differentiation of cells, and on to the evolution of specialised reproductive cells, the gametes. This development was followed by the rapid appearance of diverse animal species, from fish and amphibians to reptiles, insects, dinosaurs, birds and mammals.

In the second section, Primate Climax – which covers the period from 66 million to 315,000 years ago – we learn about the development of external genitals and the birth of “the age of the orgasm”, as well as primate sexual behaviour and social organisation.

The final section, Cultural Afterglow, which extends from 315,000 years ago to the present, traces the history of Homo sapiens from hunter-gatherers, to the first agrarian societies, and on to the present day.

The word length of each section is inversely proportional to the time scale being described – a reflection of our relative knowledge about sexual behaviour, but also its evolving complexity over time.

Sex and the single gene: new research shows a genetic ‘master switch’ determines sex in most animals

Evolution

Baker’s prose is animated and deliberately raunchy, making what would be a dense read light and entertaining. But to weave his “grand narrative of sex” he also anthropomorphises reproduction of even the earliest living organisms.

For example, explaining theory behind the first, possibly accidental, mixing of genes two billion years ago, Baker describes “Snowball Earth” – a period when the average global temperature was minus 50 degrees Celsius. His argument is that asexual reproduction at this time of catastrophic climatic conditions was causing overpopulation and that sexual reproduction would slow population growth.

This sounds counter-intuitive, but sexual reproduction takes time, much longer than simply cloning oneself. Two separate, unrelated organisms need to find each other and then exchange DNA. And it seems that the very first time this happened was what Baker describes as “cannibal sex”: one cell ingesting another due to starvation and accidentally mixing DNA. Baker thus writes:

To put it slightly more crudely, 2 billion years ago our ancestors felt so much pressure from the environment that they needed to fuck in order to survive.

A few pages later, he writes “furthermore, sex bequeathed upon those hardy, horny eukaryotes the potential for rapid evolution into increasingly complex species”.

Throughout his descriptions of sexual and reproductive behaviour of pre-primate species, Baker attributes very human characteristics to living organisms that simply don’t make sense. While this can be amusing, I also found it slightly irritating. The long bow being drawn between “sexual” behaviour involving the first exchange of DNA by single-celled organisms and the first modern humans is long indeed.

Rattiya Thongdumhyu/Shutterstock

Baker provides an interesting summary of the diversity among our primate ancestors. He notes differences in anatomy and genital size, and considers variations in practices such as masturbation and sexual partnering, including polygamy, monogamy, promiscuity, homosexual and bisexual behaviour.

He delves into the issues of pleasure, romantic love and parenting, and related forms of social organisation, such as patriarchy and matriarchy. And he considers variations, such as patrilocality (where males remain in their families and females move out to live with the male parent of their offspring) and its reverse, matrilocality.

Baker also points out that a pleasure response to copulation can be seen in fish and reptiles, similar to the sensations experienced after eating, but that the orgasm emerges with placental mammals.

It is, however, the evolution of human culture that radically changes everything. Baker condenses a few hundred thousand years of the history of human sexuality into 150 pages. He covers diversity (including intersex characteristics and gender and sexual diversity) and considers the ways in which societies have controlled sexuality and sexual behaviour through legal and other sanctions.

Central to these cultural practices is the control of female sexuality, which emerged with the development of agriculture and the need to retain land ownership and safeguard inheritance down patriarchal lines.

Guide to the classics: Darwin’s The Descent of Man 150 years on — sex, race and our ‘lowly’ ape ancestry

The future of sex

In the book’s final chapter, The Future of Sex, Baker shares his belief that “Nurture has ceased to impede the sexual impulses of Nature”, leading to a state where “loneliness is at an all-time high and personal happiness is at its lowest ebb”.

This is a sweeping statement. How did we measure loneliness and personal happiness in, say, Ancient Egypt? Do experiences of loneliness and personal happiness vary around the globe? Do they mean different things in different cultures?

Informing some of Baker’s thinking are statistics about the number of Millennials “projected to never get married in their lifetimes” and the decline in rates of casual sex. But it is not clear if they are only from studies in Western countries or how representative they are at a global level.

Baker concludes the book with four categories of future forecasts. His “projected future” is based on current observation. Here he predicts a rise in singledom and a state where promiscuity and sexlessness both exist and birth rates decline.

His “probable future” anticipates a “cultural rejection of relationships as the key to happiness”. It would involve more hook-ups and the growing replacement of human-to-human sex with sex dolls and bots. Alternatively, Baker suggests humanity might swing back towards traditional monogamous couplings, or a revival of polygyny, or a “promiscuity overdrive”.

In a “possible future”, he considers how internet technology might lead to virtual, AI-driven partnered sex. Finally, in a “preposterous future”, he suggests that sex could cease to be important to living organisms at all.

Fossiant/Shutterstock

While Baker’s deliberations are interesting and worth pondering, it is difficult to accept his claim that “the liberalisation of attitudes towards sex has released human sexuality from the grip of culture”. Indeed, the statement is something of an oxymoron, since “liberalising attitudes” are themselves a cultural phenomenon.

The “grip of culture” is still ever-present in the policing of female sexual behaviour, which continues to the present day the world over. So does the epidemic of sexual violence against women.

The other aspect of Baker’s book that I wonder about is its “knowability”. How many of the “facts” presented are really known? How much is be conjecture? While there is an impressive list of references at the end of the book, Baker admits that many of the beliefs he shares about the evolution of sex are not certain.

This speaks, in part, to the tensions that exist between “Big History” and “Deep History”. Big History presents itself as an answer to an existential question – why are we here? But, as some critics have argued, humans do not “easily fit into a Big History framework”.

Baker concludes with a statement about what he wanted to achieve in writing this book. He hopes that “some aspects of sex have become slightly less baffling for the reader” and wishes his readers the “sensation of feeling truly loved” – a kind sentiment, but slightly at odds with what has come before.

From my perspective, the world has a long way to go to achieve human rights for all in the areas of sexuality and gender. If Baker’s book helps this endeavour by getting us to think about human sexuality more deeply, then it will prove worthwhile.