Recent excavations at the Villa of the Quintilii uncovered the remains of a unique winery just outside Rome.

The mid-third-century CE building located along the Via Appia Antica portrays a sense of opulence and performance almost never found at an ancient production site.

This exciting complex illustrates how elite Romans fused utilitarian function with luxurious decoration and theatre to fashion their social and political status.

I was one of the specialist archaeologists to study this newly excavated site. The details of this discovery are outlined in our new article in Antiquity.

S. Castellani, Author provided

The Villa of the Quintilii

From names stamped on a lead water pipe, we know the 24 hectare ancient Roman villa complex was owned by the wealthy Quintilii brothers, who served as consuls in 151 CE.

Wikimedia Commons

The Roman emperor Commodus had the brothers killed in 182/3 CE.

He took possession of their properties, including this villa, initiating long-term imperial ownership.

The site has been long known for its decorative architecture, including coloured marble tiling, high-quality statuary recovered over the last 400 years, and a monumental bathing complex.

Less known is an enormous circus for chariot racing built during the reign of Commodus.

From 2017-18, during an attempt to discover the starting gates of the circus, the first traces of a unique winery were revealed.

Unearthing Falerii Novi’s secrets in the hot Italian summer: an archaeologist reports from the dig

A luxury Roman imperial winery

This large complex was built on top of the circus starting gates, which dates it after the reign of Commodus.

The complex possesses features commonly found in ancient Roman wineries: a grape treading area, two wine presses, a vat to collect grape must (the juice of the grapes along with their skins, seeds and stems) and a cellar with large clay jars for storage and fermentation sunk into the ground.

However, the decoration and arrangement of these features is almost completely unparalleled in the ancient world.

Photo by M.C.M s.r.l and adaptation in Dodd, Frontoni, Galli 2023, Author provided

Nearly all the production areas are clad in marble veneer tiling. Even the treading area, normally coated in waterproof cocciopesto plaster, is covered in red breccia marble. This luxurious material, combined with its impracticalities (it is very slippery when wet, unlike plaster), conveys the extreme sense of luxury.

E. Dodd, Author provided

Two immense mechanical lever presses sit either side of the treading area to press the already trodden grape pulp.

The size and scale of these presses working up and down in harmony would have contributed to the theatre of the production process.

The grape juice produced from treading and pressing flowed from these areas into a long rectangular vat, where an impression from a stamp named the short-reigning emperor Gordian (deposed 244 CE). This confirms a date of construction or renovation.

But it is here the real performance would have begun.

The liquid grape must poured like a striking fountain out of the vat and through a facade around one metre in height that closely resembles a Roman nymphaeum (a monumental decorated fountain).

E. Dodd, Author provided

While must flowed out of the three central niches, water flowed out of those on either end and was then channelled back underground through a system of lead pipes.

This niched facade was originally clad in a decorative veneer of brightly coloured white, black, grey and red marble. Some pieces remain attached and more were found loose in the excavated layers.

E. Dodd, Author provided

A system of thin open white marble channels conveyed the grape must from the facade into an open-air cellar area.

Here it was fed into 16 buried clay jars (dolia defossa) large enough for a person to fit inside. The remains of eight were uncovered during excavations.

Three rooms paved in opulent geometric marble tiling, like those found in other areas of the villa, were arranged around the cellar.

We might imagine the emperor and his retinue reclining, eating and watching the spectacle of production and tasting freshly pressed must.

S. Castellani, Author provided

Theatrical vintage ritual in ancient Italy

The only other example like this facility can be found at Villa Magna, 50 kilometres to the south-east near Anagni.

This similarly opulent marble-clad winery was in use just before the Villa of the Quintilii, from the early second to early third century CE, with an area for dining that enabled a view of the production spaces.

In Marcus Aurelius’ letters to his tutor Fronto, we are given a rare glimpse into the activities of Villa Magna around 140-145 CE. He describes the imperial party banqueting while watching and listening to the workers treading grapes.

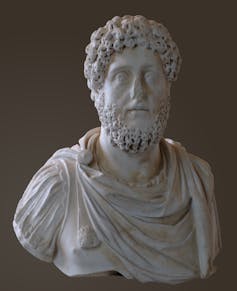

Getty Villa Museum, Malibu. Wikimedia Commons

It is likely this formed part of a vintage ritual, tied to the ceremonial opening of the harvest. Perhaps this ritual also occurred at the slightly later Villa of the Quintilii facility.

Lavish marble-clad spaces marked areas fit for the imperial party and the winery was the “theatre” for this sacred performance.

One tantalising question remains unanswered: was the Roman emperor’s spectacular, ritual winery moved in the early third century CE from Villa Magna to the Villa of the Quintilii?

Pompeii is famous for its ruins and bodies, but what about its wine?