During the COVID-19 pandemic, countries around the world restricted large gatherings to reduce the spread of the virus. Religious events, including in-person worship services, were banned in many places. In every region of the globe, at least some religious groups protested these regulations.

Pew Research Center’s 13th annual report on restrictions on religion in 2020 includes a new analysis of how public health measures related to the coronavirus affected religious groups the year the pandemic took hold globally. The report also shows that overall government restrictions and social hostilities relating to religion remained fairly stable from 2019 to 2020.

The study analyzes 198 countries and territories and is based on policies and events in 2020, the most recent year for which data is available.

These are the key findings from the report.

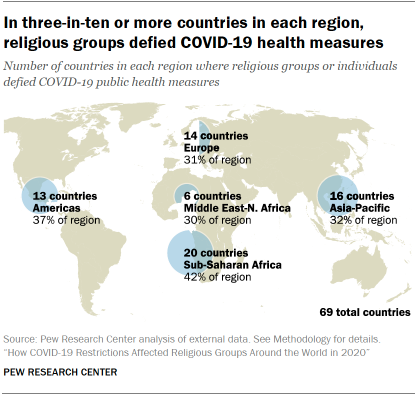

In 69 countries (35% of the total analyzed), one or more religious groups defied public health measures that were imposed during the pandemic. In Canada, for example, several congregations continued holding services despite restrictions on large gatherings to limit the spread of the coronavirus. Leaders of the Free Grace Baptist Church and Free Reformed Church in Chillwack, British Columbia, argued that restrictions on gatherings violated their rights and freedoms. And in the United States, a pastor in Louisiana challenged the governor’s stay-at-home orders by holding services at his church, telling the hundreds of attendees that they had “nothing to fear but fear itself.”

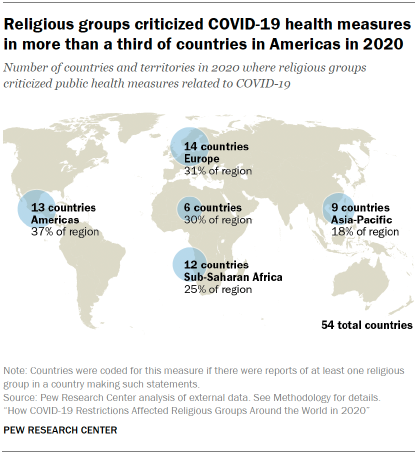

Religious groups criticized government-mandated public health measures in 54 countries (27% of all analyzed), often stating the rules were a violation of religious freedom. In 45 countries (23%), religious groups claimed that limits on large gatherings targeted them unfairly when compared with shops, restaurants or other businesses. In Belgium, for instance, about 100 Catholics asked the Council of State to nullify the suspension of all religious gatherings (other than funerals), arguing it was unfair that large crowds were allowed to go to shops but not to Mass. They argued that the rule was “disproportionate and violates religious freedom as guaranteed in the [country’s] Constitution.”

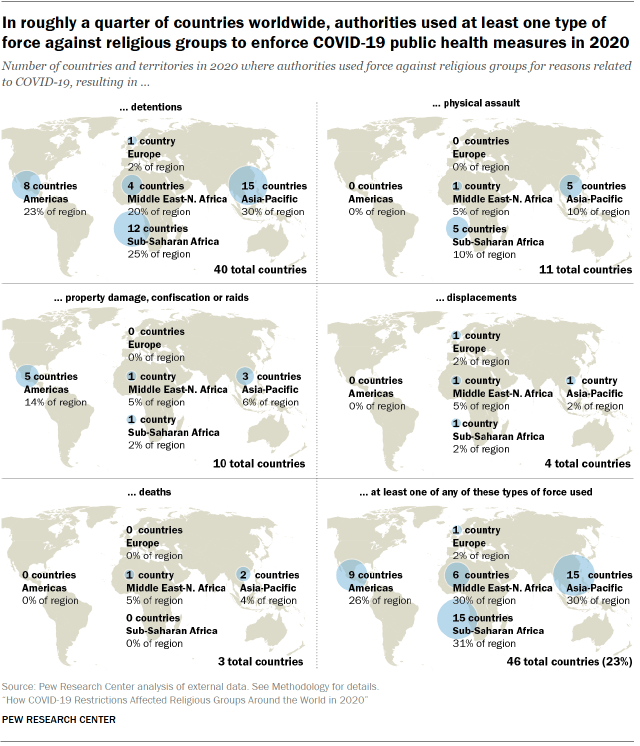

In nearly a quarter of countries, governments used physical force, such as arrests and raids, to make religious groups comply with COVID-19 public health measures. In Comoros, Gabon and Nepal, police used tear gas to disperse religious gatherings that violated COVID-19 lockdown rules. In the United States, police in New Jersey arrested 15 people at a rabbi’s funeral that violated the state’s stay-at-home order. (The arrests came after some mourners became disorderly and argumentative when police tried to turn the crowd away, according to media reports.) In South Korea, authorities raided the headquarters of the Shincheonji Church of Jesus, largely because it violated restrictions on public gatherings and its leader refused to share membership lists with authorities so they could track the spread of the virus. And in India, two Christians died after being beaten in police custody; they had been accused of violating COVID-19 curfews in the state of Tamil Nadu.

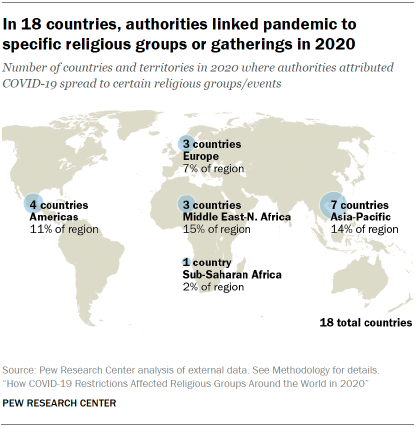

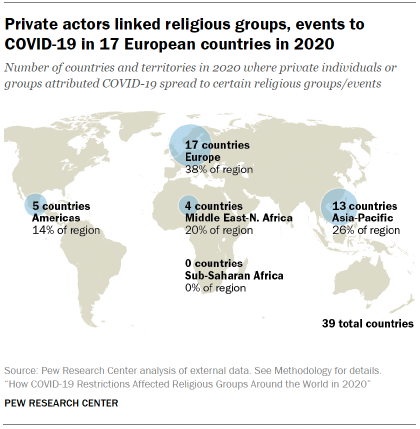

Authorities and social groups in several countries blamed religious groups for spreading the virus. In 18 countries, authorities linked religious groups or gatherings to the spread of COVID-19. And in 39 countries (20% of all studied) private individuals or groups attributed the spread of the virus to religious groups. In Pakistan, Shiite Muslims of Hazara ethnicity who returned from a pilgrimage to Iran were accused by officials in the country’s western province of spreading COVID-19, according to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. In Cambodia, which has a Buddhist majority, the Ministry of Health in March 2020 began drawing attention to Muslims by including a special category about them in infection rate data, after reports emerged that Cambodian Muslims had contracted COVID-19 at a religious gathering in Malaysia before returning to Cambodia. Afterward, some Muslims said they faced suspicion and discrimination. Some Cambodian merchants reportedly refused to sell goods to Muslims, while other non-Muslims wore masks only in the presence of Muslims.

Private groups or individuals also used conspiracy theories or other inflammatory speech to blame specific religious groups for the spread of the virus. In 23 countries, such comments targeted Jews. In France, social media users shared antisemitic tropes with caricatures of a former Jewish health minister that depicted her poisoning a well – an insinuation that Jews were responsible for the pandemic (and a reference to a trope that dates back to the 14th-century Black Plague).

Muslims were targeted by such inflammatory speech in 15 countries. In India, for example, Islamophobic hashtags like #CoronaJihad circulated widely on social media. Meanwhile, Christian groups were accused in nine countries of having spread COVID-19. In Turkey, an Armenian Orthodox church’s door was set on fire, and a man told police he did it because “they [Armenian Christians] brought the coronavirus” to Turkey, according to news reports.

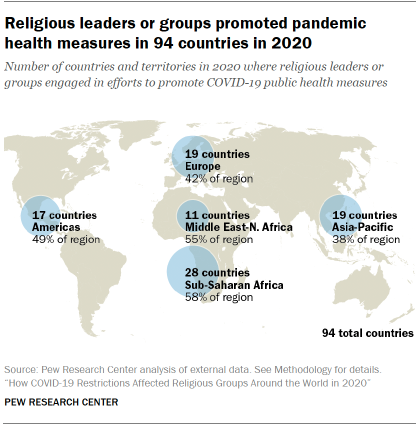

Despite the frictions over limits on large gatherings, religious groups or leaders promoted one or more types of public health measures, such as social distancing and hand-washing, in 94 (or 47%) of the countries analyzed. In Lesotho, for example, both evangelical Protestant and Catholic churches helped raise awareness about the pandemic and encouraged people to take precautions. And in Albania, religious leaders assisted the government’s health measures and canceled religious gatherings for two months.

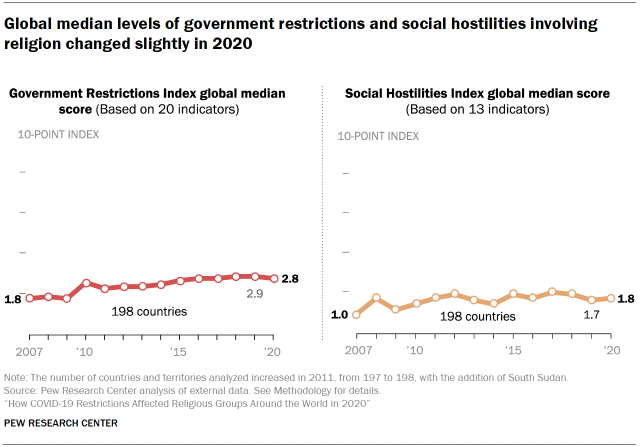

Overall, scores captured in the Center’s Government Restrictions Index (GRI) and Social Hostilities Index (SHI) remained fairly stable in 2020. The median score on the GRI – which includes laws, policies and actions by government officials that impinge on religious beliefs and practices – fell from 2.9 in 2019 to 2.8 in 2020. And the median score on the SHI, which includes religion-related hostilities by private individuals and organizations, increased slightly from 1.7 in 2019 to 1.8 in 2020. (Scores on both indexes range from 0 to 10).

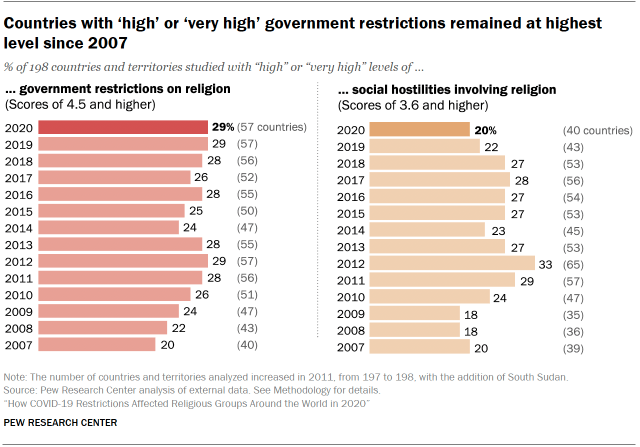

Meanwhile, the number of countries with either “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions remained the same, at 57 countries (29%) from 2019 to 2020, a peak number for the study. At the same time, the number of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities fell from 43 countries (22%) in 2019 to 40 countries (20%) in 2020, which was below the peak of 65 countries (33%) recorded in 2012.

Note: For a list of the global news sites and organizations used and more details on sources used in the study, read the methodology.