“Jesus Christ was a sportsman.” Or so claimed a preacher at one of the regular sporting services that were held throughout the first half of the 20th century in Protestant churches all over Britain.

Invitations were sent out to local organisations, and sportsmen and women would attend these services en masse. Churches would be decorated with club paraphernalia and cups won by local teams. Sporting celebrities – perhaps a Test cricketer or First Division footballer – would read the lessons, and the vicar or priest would preach on the value of sport and the need to play it in the right spirit. Occasionally, the preacher would himself be a sporting star such as Billy Liddell, the legendary Liverpool and Scotland footballer.

Since 1960, however, the trajectories of religion and sport have diverged dramatically. Throughout the UK, attendances for all the largest Christian denominations – Anglican, Church of Scotland, Catholic and Methodist – have fallen by more than half. At the same time, the commercialisation and televisation of sport has turned it into a multi-billion dollar global business.

This article is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism derived from interdisciplinary research. The team is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

Numerous high-profile sporting stars talk openly about the importance of religion to their careers, including England footballers Marcus Rashford, Raheem Sterling and Bukayo Saka. World heavyweight boxing champion Tyson Fury credits his Catholic faith with bringing him back from obesity, alcoholism and cocaine dependency.

Yet it is sport, and its “gods” like Fury, that attracts far greater devotion among much of the public. Parents are as anxious today to ensure their children spend Sunday mornings on the pitch or track as they might once have been to see them in Sunday school.

But to what extent is the worship of sport, and our regular pilgrimages to pitches and stadiums up and down the country, responsible for the emptying of churches and other religious establishments? This is the story of their parallel, and often conflicting, journeys – and how this “great conversion” changed modern society.

Gene Blevins/Zuma Wire/Alamy

When religion gave sport a helping hand

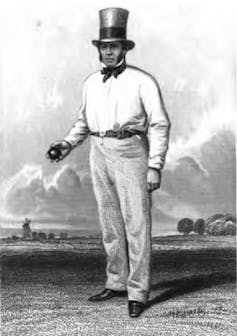

Two hundred years ago, Christianity was a dominant force in British society. In the early 19th century, as the modern sporting world was just beginning to emerge, the relationship between church and sport was mainly antagonistic. Churches, especially the dominant evangelical Protestants, condemned the violence and brutality of many sports, as well as their association with gambling.

Many sports were on the defensive in the face of religious attack. In my book Religion and the Rise of Sport in England, I chart how sport’s advocates – players and commentators alike – responded with verbal and even physical attacks on religious zealots. In 1880, for example, boxing historian Henry Downes Miles celebrated novelist William Thackeray’s stirring descriptions of the “noble art” while also bemoaning religion’s attempts to curb it:

[This description of boxing] has lines of power to make the blood of your Englishman stir in days to come – should the preachers of peace at-any-price, parsimonious pusillanimity, puritanic precision and propriety have left our youth any blood to stir.

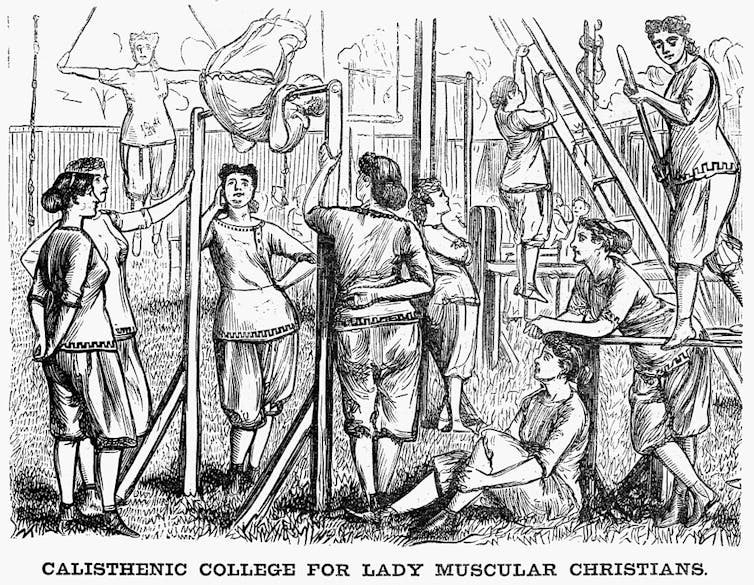

Yet around this time, there were also the first signs of a rapprochement between religion and sport. Some churchmen – influenced both by more liberal theologies and the nation’s health and societal failings – turned from condemning “bad” sports to promoting “good” ones, notably cricket and football. Meanwhile the new Muscular Christianity movement appealed for recognition of the needs of “the whole man or whole woman – body, mind and spirit”.

Granger Collection, CC BY

By the 1850s, sport had become central to the curricula of Britain’s leading private schools. These were attended by many future Anglican clergymen, who would go on to bring a passion for sport to their parishes. No fewer than a third of the Oxford and Cambridge University cricket “blues” (first team players) from the years 1860 to 1900 were later ordained as clergy.

While the UK’s Christian sporting movement was pioneered by liberal Anglicans, other denominations (plus the YMCA and, a little later, the YWCA) soon joined in. In an editorial on The Saving of the Body in 1896, the Sunday School Chronicle asserted that “the attempted divorce of the body and soul has ever been the source of the keenest woes of mankind”.

It explained that, unlike medieval saints’ instances of extreme bodily mortification, Jesus came to heal the whole man – and therefore:

When the religion of the gymnasium and the cricket-field is duly recognised and inculcated, we may hope for better results.

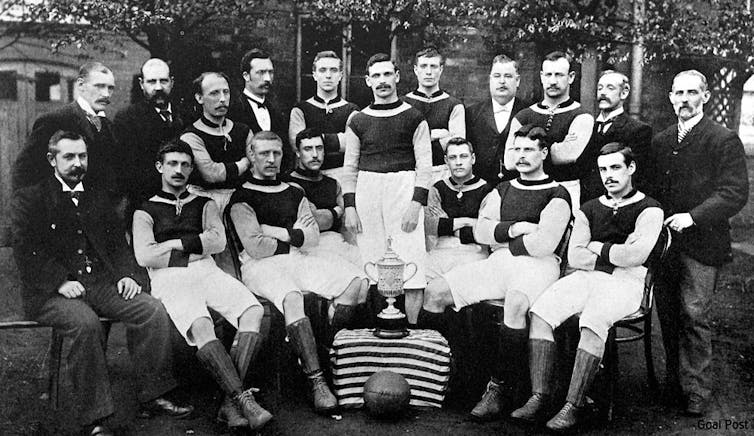

Religious clubs were formed, mostly strictly for fun and relaxation on a Saturday afternoon. But a few went on to greater things. Aston Villa football club was founded in 1874 by a group of young men in a Methodist bible class, who already played cricket together and wanted a winter game. Rugby union’s Northampton Saints started six years later as Northampton St James, having been founded by the curate of the town’s St James Church.

Henry Joseph Whitlock/Wikimedia

Meanwhile, Christian missionaries were taking British sports to Africa and Asia. As J.A. Mangan describes in The Games Ethic and Imperialism: “Missionaries took cricket to the Melanesians, football to the Bantu, rowing to the Hindu [and] athletics to the Iranians”. Missionaries were also the first footballers in Uganda, Nigeria, the French Congo and probably Africa’s former Gold Coast too, according to David Goldblatt in The Ball is Round.

Wikimedia

But at home, religious denominations and their members responded selectively to the late Victorian sporting boom, adopting some sports while rejecting others. Anglicans, for example, enjoyed a love affair with cricket. One of the first books celebrating it as England’s “national game” was The Cricket Field (1851) by Rev. James Pycroft, a Devon clergyman who pronounced: “The game of cricket, philosophically considered, is a standing panegyric to the English character.”

Admittedly, Pycroft also noted a “darker side” to the game, arising from the large amount of betting on cricket matches at that time. But, in a claim that would be made for many other sports over the next century and a half, he suggested it was still a “panacea” for the nation’s social ills:

Such a national game as cricket will both humanise and harmonise our people. It teaches a love of order, discipline and fair-play for the pure honour and pure glory of victory.

Meanwhile, Jews came to the fore in boxing in Britain – in contrast to the nonconformists who mainly opposed boxing because of its violence, and who were totally against horse racing because it was based on betting. They approved of all “healthy” sports, though, and were enthusiastic cyclists and footballers. In contrast, many Catholics and Anglicans enjoyed horse racing and also boxed.

But as the 19th century neared its end, the most hotly debated issue was the rise of women’s sport. Unlike in other parts of Europe, however, there was little religious opposition to women taking part in Britain.

From the 1870s, upper and upper-middle-class women were playing golf, tennis and croquet, and not long afterwards sport entered the curricula of girls’ private schools. By the 1890s, the country’s more affluent churches and chapels were forming tennis clubs, while those with a broader social constituency formed clubs for cycling and hockey, most of which welcomed both women and men.

Wikimedia

The involvement of churches in amateur sport would peak in the 1920s and 30s. In Bolton in the 1920s, for example, church-based clubs accounted for half of all teams playing cricket and football (the sports most widely practised by men) and well over half those playing hockey and rounders (typically practised by women).

At this time, an extensive sporting programme was so taken for granted in most churches that it scarcely needed a justification. However, there was a gradual decline in church-based sport after the second world war – which became much more rapid in the 1970s and ’80s.

When sport became ‘bigger than religion’

Even before the dawn of the 20th century, critics of private schools and universities were complaining that cricket had become “a new religion”. Similarly, some observers of working-class cultures were concerned that football had become “a passion and not merely a recreation”.

The most obvious challenge that the rise of sport presented for religion was competition for time. As well as the general problem that both are lengthy pursuits, there was the more specific problem of the times when sport is practised.

Jews had long faced the question of whether playing or watching sport on a Saturday is compatible with observance of the Sabbath. From the 1890s, Christians began to face similar issues with the slow-but-steady growth of recreational sport and exercise on Sundays. The bicycle provided the perfect means for those who wanted to spend the day outdoors, far from church, and golf clubs were beginning to open on Sundays too – by 1914, this extended to around half of all English golf clubs.

But unlike in most other parts of Europe, professional sport on Sundays remained rare. This meant that Eric Liddell, the Scottish athlete and rugby union international immortalised in the film Chariots of Fire, could quite easily combine his brilliant sporting career with a refusal to run on Sundays, so long as he remained in Britain. When the 1924 Olympics were held in Paris, however, Liddell famously refused to compromise by taking part in the Sunday heats for the 100m sprint. He went on to win 400m gold instead, before returning to China the following year to serve as a missionary teacher.

The 1960s finally marked the beginning of the end for Britain’s “sacred” Sunday. In 1960, the Football Association lifted its ban on Sunday football, leading to the formation of numerous Sunday leagues for local clubs. The first Sunday matches between professional teams took rather longer, starting with Cambridge United v Oldham Athletic in the third round of the FA Cup on January 6 1974. Before then, in 1969, cricket had become the first major UK sport to stage elite-level Sunday sport with its new 40-over competition – sponsored by John Player cigarettes and televised by the BBC.

But perhaps the clearest indicator of the growing perception of sporting sites as “sacred spaces” was the practice of scattering supporters’ ashes on or close to a pitch. This gained particular popularity in Liverpool during the reign of the football club’s legendary manager Bill Shankly (1959-74), who is quoted in John Keith’s biography explaining the reasoning behind it:

My aim was to bring the people close to the club and the team, and for them to be accepted part of it. The effect was that wives brought their late husbands’ ashes to Anfield and scattered them on the pitch after saying a little prayer … So people not only support Liverpool when they’re alive. They support them when they are dead.

Shankly’s own ashes were scattered at the Kop end of the Anfield pitch following his death in 1981.

Garry Bowden/PHC Images/Alamy

By now, sporting enthusiasts were happy to declare – and elaborate on – their “sporting faith”. In 1997, lifelong Liverpool fan Alan Edge drew an extended parallel between his upbringing as a Catholic and his support for the Reds in Faith of Our Fathers: Football as a Religion. With chapter titles such as “Baptism”, “Communion” and “Confession”, Edge offers a convincing explanation of why so many fans say that football is their religion, and how this alternative faith is learnt:

I’m attempting to provide an insight into some of the reasons behind all the madness; why people like me turn into knee-jerking, football crazy lunatics … It is a story that could apply equally to fans from any of the other great footballing hotbeds … All are places where cradle-to-grave indoctrination is part of growing up; where football is a primary – at times, the primary – life-force, supplanting religion in the lives of many.

‘Sport does things religion no longer offers’

Whether as participant or supporter, many people’s loyalty to sport now provides a stronger source of identity than the religion (if any) to which they are nominally attached.

When writing about his experiences of long-distance running, author Jamie Doward suggests that, for him and many others, running marathons does some of the things that religion can no longer offer. He calls running “the secular equivalent of the Sunday service” and “modernity’s equivalent of a medieval pilgrimage”, adding:

It is perhaps no surprise that the popularity of running is increasing as that of religion declines. The two appear coterminous, with both delivering their own forms of transcendence.

In turn, sport has narrowed down the societal space traditionally occupied by religion. For example, the belief held by governments and many parents that sport can make you a better person has meant that sport frequently takes over the role formerly performed by churches of seeking to produce mature adults and good citizens.

In 2002, Tessa Jowell, then secretary of state for culture, media and sport, introduced the Labour government’s new sport and physical activity strategy, Game Plan, by claiming that increased public participation could reduce crime and enhance social inclusion. She added that international sporting success could benefit everyone in the UK by producing a “feel-good factor” – and a year later confirmed that London would bid to host the 2012 Olympics.

Amid its growth, however, sport also had to cope with regular controversies that seemingly threatened to reduce its appeal. In 2017, at a time of widespread public concern about drug-taking in athletics and cycling, betting and ball-tampering in cricket, deliberate injuring of opponents in football and rugby, and physical and mental abuse of young athletes in football and gymnastics, a headline in the Guardian read: “General public is losing faith in scandal-ridden sports”. Yet even then, the referenced poll found that 71% of Britons still believed that “sport is a force for good”.

Diocese of Derby Communications/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Religious organisations have responded in different ways to the role of sport in contemporary society. Some, like the current bishop of Derby Libby Lane, see it as presenting opportunities for evangelism – if that is where the people are, the church should be there too. In 2019, following her appointment as the Church of England’s new bishop for sport, Lane told the Church Times:

Sport may be a way of growing the Kingdom of God for the Church … It shapes our culture, our identity, our cohesion, our wellbeing, our sense of self, and our sense of place in society. If we are concerned about the whole of human life, then for the Church to have a voice in [sport] is vital.

The sports chaplaincy movement has also grown significantly since the 1990s – notably in football and rugby league, where it is now a standard post in most major clubs. And at the London Olympics in 2012, there were 162 working chaplains belonging to five religions.

A chaplain’s role is to provide personal support for people working in a difficult profession, many of whom have come from distant parts of the world. In the early 2000s, the chaplain of Bolton Wanderers asked the football club’s players about their religions. As well as Christians and those with no religion, the squad included Muslims, a Jew and a Rastafarian.

But in addition to reflecting the rapid internationalisation of many professional dressing rooms, chaplains’ increased adoption by sports teams may reflect growing recognition of the mental as well as physical toll that elite sport can take.

Meanwhile, the proliferation of Muslim cricket leagues and other Muslim sporting organisations in Britain is in part a response to threats and challenges, including racism and the widespread drinking culture of some sports. The recent formation of the Muslim Golf Association reflects the fact that, although the explicit exclusion which Jewish golfers faced in earlier times would now be illegal, Muslim golfers still feel unwelcome in some UK golf clubs.

And UK sporting organisations for Muslim women and girls, such as the Muslim Women’s Sports Foundation and the Muslimah Sports Association, are a response not only to prejudice and discrimination by non-Muslims but to the discouragement they may encounter from Muslim men. A Sport England report in 2015 found that, while Muslim male players were more active in sport than those from any other religious or non-religious group, their female counterparts were less active than women from any other group.

Marco Iacobucci Epp/Shutterstock

Of course, religious differences have long contributed to tensions and, in some cases, violence both on and off the pitch – most famously in Britain through the historic rivalry between Glasgow’s two biggest football clubs, Rangers and Celtic. In 2011, Celtic manager Neil Lennon and two prominent fans of the club were sent parcel bombs intended to kill or maim.

Duncan Morrow, a professor who chaired an independent advisory group on tackling sectarianism in Scotland in response to these heightened tensions, identified a fascinating shift in religion’s relationship with sport:

In a time where religion is less important in society, it is almost as if it has become part of the identity of football in Scotland. In a sense, sectarianism now is a way of behaving rather than a way of believing.

Why many elite athletes still rely on religion

In the early 2000s, the Muslim ethos of the Pakistan cricket team was so strong that the only Christian player, Yousuf Youhana, converted to Islam. The chairman of the Pakistan Cricket Board, Nasim Ashraf, wondered aloud if things had gone too far. “There is no doubt,” he said, “religious faith is a motivating factor for the players – it binds them together.” But he also worried that undue pressure was being put on less devout players.

In more pluralistic and secular societies, the use of religion to bond a team together may prove counterproductive. But it is still vitally important for many sportsmen and women.

Faith-driven athletes find in their reading of the Bible or the Qur’an, or in their personal relationship with Jesus, the strength to face the trials and tribulations of elite sport – including not only the disciplines of training and of overcoming physical pain, but also the bitterness of defeat.

[email protected]/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

One of the best-known examples of how a leading athlete drew on his religion is Britain’s world record-holding triple jumper Jonathan Edwards, who spoke frequently about his evangelical Christian belief during his days of competing. (Edwards would later renounce his faith following his retirement, claiming that it had acted as the most powerful kind of sports psychology.)

As well as strengthening his drive to succeed and helping him bounce back from defeat, Edwards also felt an obligation to speak about his faith. Or as his biographer put it:

Jonathan felt he was answering a call to be an evangelist – a witness to God in running shoes.

Athletes from religious minorities frequently see themselves as symbols and champions of their own communities. Thus, Jack “Kid” Berg, world light welterweight boxing champion in the 1930s, entered the ring with a prayer shawl round his shoulders and wore a Star of David during each fight. More recently, the England cricketer Moeen Ali has been a hero for many Muslims, yet provoked the ire of one Daily Telegraph journalist who is said to have told him: “You are playing for England, Moeen Ali, not for your religion.”

The stresses arising from failure in elite sport – and the value of faith in dealing with them – have also been highlighted in the career of British athlete Christine Ohuruogu, who won 400m gold at the 2008 Olympics having earlier been banned for a year for allegedly missing a drug test:

Among the athletic victories, Christine has had to cope with numerous injury problems, the indignity of disqualification, and cruel false allegations in the tabloid press. Christine says that it is her strong faith in God which has sustained her.

John Walton/PA/Alamy

And England rugby union star Jonny Wilkinson claimed that 24 hours after the last-minute drop goal which won the World Cup for England in 2003, he was overcome with “a powerful feeling of anti-climax”. He later explained in an interview with the Guardian that he found the solution through his conversion to Buddhism:

It’s a philosophy and way of life that resonates with me. I agree with so much of the sentiment behind it. I enjoy the liberating effect it’s had on me to get back into the game – in a way that’s so much more rewarding because you’re enjoying the moment of being on the field. In the past it was basically me getting into the changing room, wiping my brow and thinking: “Thank God that’s over.”

While sport has assumed a place in society that religion once filled for many, the questions that religions seek to answer have not gone away – not least for elite athletes. For them, sport is a profession and a very demanding one, and a significant number find strength and inspiration through their faith.

Of course, many of today’s UK-based sporting professionals hail from less secularised regions of the world, while others are the children of immigrants and refugees. The 2021 census found that both the absolute number and proportion of Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists and those selecting “other religion” had all increased in England and Wales over the previous decade.

London’s Olympic legacy: research reveals why £2.2 billion investment in primary school PE has failed teachers

So we are left with something of a paradox. While religion has been crowded out by sport in general society, it remains a conspicuous part of elite sport – with a number of studies around the world finding that athletes tend to be more religious than non-athletes.

The Church of England is aware of this contrast, and has responded by launching a National Sport and Wellbeing project, piloted in eight of its dioceses. Despite launching just before the pandemic, initiatives have included adapting church premises for football, netball and keep-fit sessions, formation of new sports clubs aimed especially at non-churchgoers, and after-school clubs and summer holiday camps that offer a combination of sport and religion.

In fact, the agenda is more explicitly evangelistic than in the Victorian days of Muscular Christianity. Those engaging in today’s “sports ministry” are well aware of the challenges they face. Whereas in later Victorian times and the first half of the 20th century, many people had a loose connection with the church, now the majority have no connection at all.

But today’s religious evangelists display a strong faith in sport. They believe it can help build new connections, particularly among younger generations. As the Church of England’s outreach project concludes:

This has a huge mission potential … If we are to find the sweet spot [between sport and religion], it could contribute to a growing and outward-facing Church.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.