When the eminent Australian anthropologist W. E. H. Stanner first published his essay on “The Dreaming” in 1956, there was increasing scholarly and popular interest in the complexity and duration of Australia’s Indigenous cultures.

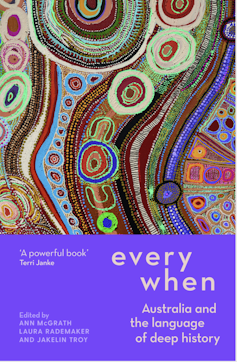

Everywhen: Australia and the language of Deep History – edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker and Jakelin Troy (UNSW Press)

That same year, an excavation by the archaeologist D. J. Mulvaney at Fromm’s Landing in South Australia utilised radiocarbon dating for the first time in Australia. It verified human occupation of that site stretching back 5,000 years.

This might feel slim by today’s understanding of Indigenous ancientness, but in the 1950s and 1960s, scientific dating confirmed Australia’s human history reached well beyond any sort of written archival record. Moving Australian History into the deep past, thousands of years before colonisation brought with it Western forms of history-making, established a radical new timescale for the discipline.

Jim Bowler’s famous work at Lake Mungo in south-western New South Wales in the 1960s and 1970s pushed back the date of Aboriginal occupation even further – to an extraordinary 40,000 years. By the early 21st century, Aboriginal claims that they had always been here didn’t seem unreasonable alongside archaeological finds that measured their presence at 65,000 BCE.

65,000-year-old plant remains show the earliest Australians spent plenty of time cooking

As well as comprehending that colossal timescale, there has been the challenge of how to acknowledge and translate the understandings and experiences of time held by Australia’s First Peoples. Since Baldwin Spencer and James Gillen’s ethnological work in the late 19th century, the term “Dreamtime”, or “Dreaming” had been variously applied to this variegated Indigenous time: at once now and then, both cosmological and narrative-truth.

In Stanner’s 1956 essay, “The Dreaming”, he attempted to tease out a translation of Indigenous temporality. “The Dreaming conjures up the notion of a sacred, heroic time of the indefinitely remote past, such a time is also, in a sense, still part of the present”, he suggested. “One cannot ‘fix’ The Dreaming in time: it was, and is, everywhen.”

Everywhen.

It was a bold, memorable term. Stanner’s attempt to bring Indigenous knowledges into an Australian public discourse reflected his belief in the importance of understanding Aboriginal history and history-making.

Over 50 years later, that commitment to translation and conversation is the focus of an impressive collection of essays, Everywhen, edited by Ann McGrath, Laura Rademaker and Jakelin Troy. “The concept of everywhen,” they explain, “unsettles the way historians and archaeologists have conventionally treated time — as a linear narrative that moves toward increasing progress and complexity.”

The volume looks back on that original attempt at translation by Stanner and others, but also renegotiates the terms of the conversation around Indigenous deep histories and conceptions of time.

“We take ‘deep history’ to include the histories that long precede modernity, the medieval era and the few thousand years generally known as ancient history”, McGrath and Rademaker explain in the book’s introduction. But this is more than simply going back in time, they add:

we consider that deep history is largely Indigenous history, so it cannot be slotted into European history’s existing archival boxes or temporalities.

This book is a collective act of translation and negotiation.

Translating time

Clint Bracknell describes various Noongar words for time and the past, including the illuminating term nyidiŋg, which means “long ago/cold” – pointing perhaps to a cultural memory of the last Ice Age.

Ngarigu woman and linguistic anthropologist Jakelin Troy locates time in Country itself. “We do not see ourselves as being in a solely terrestrial space”, she offers.

Land, water, and sky all connect as one space, and the stories of ancestral figures and the creation of features on the land, in the water, and in the sky are all connected.

Shannon Foster, a D’harawhal knowledge keeper, also explores the uniqueness of D’harawhal historical connections that sit outside Western conceptions of linear time. “There is no purpose for us as D’harawhal people to know a time or an age”, Foster insists. “Dates add nothing to our culture … We know their value. It has nothing to do with time”.

Specific terms shared in the book, such as the well-cited word jukurrpa in Warlpiri, as well as bugarrigarra (from the Yawuru language in the West Kimberley), and amalawudawarra (from Anindilyakwa, on Groote Island) confirm the encompassing, fluid and cosmological hues of Indigenous languages that meld time and place through Ancestors and Country.

Stephanie Flack/AAP

The collection includes multiple contributions to this conversation – from historians, archaeologists, linguists, and anthropologists, as well as Indigenous knowledge-holders. Taken together, the chapters reflect the diversity and breadth of this growing interest in deep time. Most of all, it displays a commitment to a vital conversation that has extended Australian history into the deep past and into new epistemological territory.

The ethical imperative of this exercise in translation and conversation drives the collection. As McGrath and Rademaker explain,

for most of the 20th century the way many national histories were taught in schools and publicly memorialised was as if nothing much happened until Europeans arrived.

What’s more, these histories also “fulfilled a substantive legal function” by depicting pre-colonial Australia as an “empty land” with “no history”. Sovereignty was imported, rather than recognised as held by Indigenous people.

Historians complicit

Historians have increasingly grappled with the knowledge that their discipline has been complicit in the colonisation of Indigenous peoples – policing whose histories can be told, and how. “Time” has been a critical component of that colonising architecture, as Dipesh Chakrabarty and Priya Satiya have shown — determining Indigenous people had “no time”, or existed outside historical, linear time (and therefore outside historical “progress”).

The book that changed me: how Priya Satia’s Time’s Monster landed like a bomb in my historian’s brain

In early histories of Australia, for example, historical time was understood to begin at the point of European “discovery”. Before that, the continent was in a sense “timeless” – and certainly devoid of history in a disciplinary sense.

This was “a country without a yesterday”, the writer Godfrey Charles Mundy insisted in 1852. A generation later, George Hamilton similarly described Australia and its First Peoples as essentially blank: “Here was a country without a geography, and a race of men without a history.”

Australia’s historiographical emptiness prior to colonisation — its “historylessness” as the postcolonial studies scholar Lorenzo Veracini evocatively describes it – reflected the enduring assumption that pre-colonial Australia was also pre-historical.

And yet, as this collection demonstrates, there was history, in the sense that pre-colonial Australia has a rich human past. What’s more, there were fully developed temporalities that encompassed a rich cosmology, sense of time and “code of truth”, as Worimi historian John Maynard carefully explains in his chapter.

An act of reckoning

In part, the commitment to translating, understanding and respecting “everywhen” is an act of reckoning on the part of academic history, which tended to marginalise Indigenous pasts and their expression until the 1960s and 1970s.

There is an explicit sense in this volume of the obligation to recover the deep past and engage Indigenous temporalities, without relegating them to a sort of “dreamtime” that is only mystical and spiritual. Critically, it also highlights the generosity of Indigenous historians, writers and knowledge-keepers who continue to share that knowledge, despite occlusion from the discipline for the better part of two centuries.

That’s not to say all the curly questions are answered, or reconciled. Clearly, there is a question as to how Australian Indigenous texts — drawn in sand, sung, painted, etched and walked on Country — can be rendered into scholarly historical discourse.

Or, indeed, if they should be: I couldn’t help but wonder, does the history discpline’s reach into Indigenous deep time threaten to colonise a space which has so far eluded Western epistemology? (Although, the cost of not trying might be even worse.)

Daniel Rowland/AAP

And the question of whether (and how) Western historical narratives can populate deep history with actual lives, as well as understand and represent the thoughts, feeling and senses of people who lived thousands of years ago, is still to be answered.

This uncertainty is not unique to Australia, as a recent statement on decolonising research by the American Historical Review makes clear. The ethical demand to engage with, acknowledge and include Indigenous forms of history has extended the discipline into new, albeit sometimes challenging, epistemological territory around the world.

Yet that difficult terrain can also make for the most productive conversations, as this generous volume demonstrates.