Photographer Ernest Cole was born in 1940 in the Pretoria township of Eersterust, just before apartheid was formally introduced in South Africa in 1948.

He was 20 when thousands of people gathered outside a police station in Sharpeville township to protest against being forced to carry pass books by the white minority government. On that day at least 69 people were shot dead, hundreds were injured, and a state of emergency was declared. The Sharpeville Massacre is regarded as a turning point in the struggle for liberation in South Africa. It marked the beginning of a decades-long period in which images of human rights abuses in South Africa would rarely be out of the international news.

Cole’s images were prominent in this coverage. But, unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not focus on documenting protests.

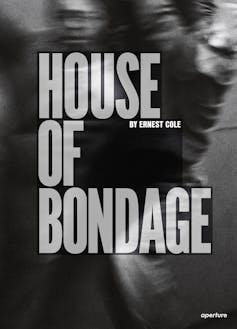

Aperture Foundation

Instead, Cole produced hundreds of photographs that portrayed the structural violence of apartheid in fine detail. He aimed to publish these images in a photobook that he intended to circulate internationally. In 1966, Cole left South Africa on an exit permit. He would never return.

House of Bondage, Cole’s unflinching and comprehensive indictment of apartheid, was published in 1967 in the US and then in the UK. When it first appeared, the photobook was banned in South Africa but some of its images found their way back into the country through resistance publications.

Santu Mofokeng: master photographer who chased down shadows

The book is now widely available again, with a new edition on the market. It returns Cole’s profound visual essay to the public eye and draws attention to his incisive critique of the violence of everyday life under apartheid.

A landmark book

After leaving South Africa, Cole continued to work as a photographer in the US and spent time in Sweden. By the 1980s, House of Bondage was out of print. The whereabouts of the photographs he produced in the US in the 1960s and 1970s – some commissioned by the Ford Foundation and the United States Information Agency – remained unknown. Then, in 2017, at least part of his archive was located in Sweden and returned to Cole’s family.

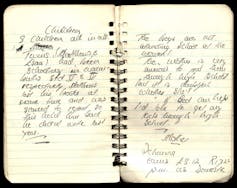

The resurfacing of more than 60,000 negatives as well as other documents, including notebooks, has led to the publication of the new edition of Cole’s landmark book by the Aperture Foundation.

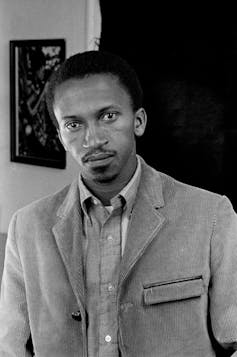

© Ernest Cole Family Trust/Wits Historical Papers/Photography Legacy Project

It includes three new introductory essays, but the core of the book remains unchanged, a deliberate, relentless journey through the broken world apartheid made. It’s divided into 15 sections including The Mines; Police and Passes; Education for Servitude; Heirs of Poverty; and Banishment, all seen through Cole’s unblinking eye.

The new edition also contains a section of previously unpublished images that Cole appeared to have intended for House of Bondage, but may have omitted in order not to detract from the work’s primary message. This section, Black Ingenuity, includes 30 photos of musicians, dancers, artists and boxers. They convey how spaces of sociality and creativity were forged in spite of apartheid.

The homecoming

A selection of the material returned to the Cole family has been digitised and made available online by the Photography Legacy Project and the Historical Papers Research Archive.

Among Cole’s hundreds of letters and press cuttings is a tattered notebook of handwritten observations about the hardships of black life under apartheid. In this small book Cole chronicles the experiences of those he met during his quest to exhaustively document South Africa’s dehumanising “crucible of racism”.

© Ernest Cole Family Trust. Courtesy Wits Historical Papers/Photography Legacy Project

Cole reveals himself to be a gifted journalist with a keen eye for the particular and the archive reveals the extensive research that went into making House of Bondage. His careful notes include the stories of mothers, workers and teachers … How a young man lost his passbook and was too afraid to report it and so could not write his exams. Why there are no desks and chairs for the children at school. How a woman has only ever been able to buy a single skirt for herself during her entire working life.

Ernest Cole/© Ernest Cole Family Trust. Courtesy Wits Historical Papers/Photography Legacy Project

Cole spent decades as a stateless person and, tormented by the racism he endured in South Africa as well as in the US and Europe, suffered psychological breakdowns. From the mid-1970s, he was homeless and spent time living in the subways in New York and occasionally at a shelter or the houses of friends. He died of pancreatic cancer in exile in 1990.

A better world

In his essay in the new edition of House of Bondage, anti-apartheid activist and poet Mongane Wally Serote observes:

No matter the very dire challenges of being poor, discriminated against, and being, by law, objects of exploitation and oppression, the people in the photographs by Ernest Cole claim life and living.

He cuts to the heart of Cole’s project: the imperative to make a better world. He argues that to see these images is not only to be reminded of the brutality of apartheid but to be shocked into recognising how the structural violence of the past lives on:

Of course, the question which must follow after seeing the horror depicted in Cole’s photographs is: why, why if there are human beings living in horror, have those conditions not been challenged and changed? Why, why are those conditions so persistent?

At least part of the answer to Serote’s lament lies in the fact that those responsible for engineering and implementing the iniquitous apartheid system have never been held to account. Cole’s book is a powerful reminder not only of what apartheid was, but of the work that remains to be done in order to dismantle the house of bondage.