More than 95% of Australian animals are invertebrates (animals without backbones – spiders, snails, insects, crabs, worms and others). There are at least 300,000 species of invertebrate in Australia. Of these, two-thirds are unknown to western science.

This means there are huge gaps in our knowledge of Australia’s invertebrates. Our new study, published today in the journal Cambridge Prisms: Extinction, indicates there has been a catastrophic under-recording of Australia’s species extinctions.

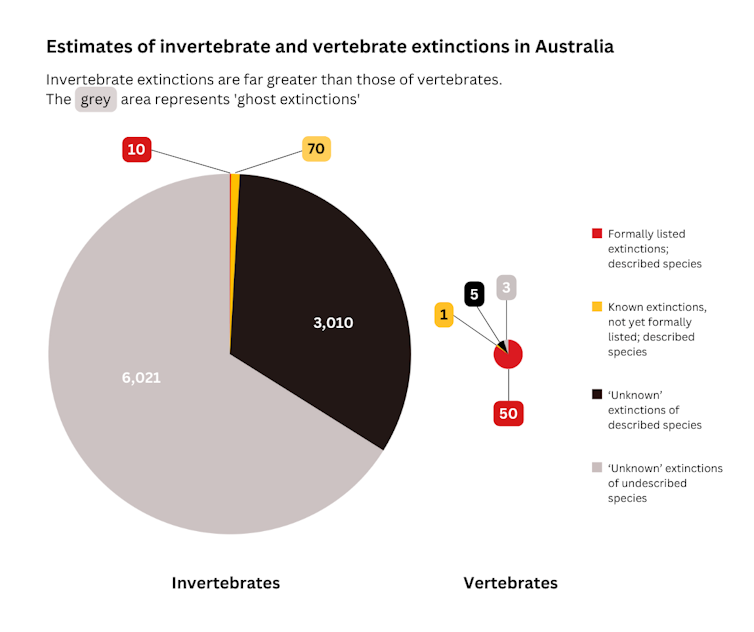

Our best estimate is that 9,111 invertebrate species have become extinct in Australia since 1788. This dwarfs the current official estimate of the total number of extinctions across all plant and animal species in Australia: 100.

The extinction of so many invertebrate species is not an arcane concern for those few people who care about bugs. Invertebrates are the building blocks of almost all ecological systems.

Loss of invertebrates will destabilise those systems. It will negatively impact the resources we depend upon, like pollination, cycling of nutrients into the soil, clean air and waterways.

Robert Speirs, Capital Ecology

Re-calculating the loss

To date, assessments of historic and ongoing biodiversity loss in Australia have been heavily skewed towards vertebrates, especially mammals and birds. This bias has also driven the efforts to prevent the loss of such species.

These conservation efforts are important. But in having such a focus, we have neglected the invertebrates. We haven’t adequately recognised which invertebrates are at the highest risk of extinction, or which have already been lost.

The most widely used estimate for the total number of extinctions of all Australian plants and animals since 1788 is “just” 100 species.

Of these, only ten are invertebrates. And only one invertebrate species, the Lake Pedder earthworm, is officially listed as extinct by the Australian government.

In our study, we used a range of approaches to estimate a more realistic figure for the number of invertebrate extinctions, and to predict how many will become extinct in 2024.

We took the proportional extinction rates of Australian vertebrates and plants and extrapolated this to the number of Australian invertebrates. Separately, we also extrapolated the proportion of extinctions recognised among all of the world’s invertebrates to the number of Australian ones.

To estimate the current extinction rate – the number of invertebrates that are going extinct as you read this article – we had to make assumptions. One option was that our estimated number of extinctions from 1788 to 2024 fell equally across the years.

However, it’s more likely the annual rate of extinctions of Australian invertebrates has increased over time. This is due to increasing habitat loss and other threats as Australia’s human population has grown.

David A. Young

Any such study will have many unknowns, unavoidable uncertainties and caveats. Because of this, we derived broad bounds to our estimate of Australian invertebrate extinctions. It ranges from about 1,500 species at the lower end to nearly 60,000 at the upper end.

This vast number of extinctions is not simply a historical blemish. Importantly, we estimate that the current rate of extinctions of Australian invertebrates is between one and three species every week.

Most of the Australian invertebrate species that have gone extinct will not yet have been formally described. Many may never be so. We have coined the term “ghost extinctions” for those species that have been lost without a trace – with no evidence they ever existed.

Jess Marsh

Why so many extinctions?

Many of the factors that have caused extinctions in Australian plants and vertebrates also threaten invertebrates. These include extensive habitat destruction, invasive species, degradation and transformation of aquatic environments, and changed fire regimes.

For invertebrates, added to that cocktail of threats is the widespread use of insecticides, pesticides and herbicides.

Many invertebrates are at high extinction risk because they live in small areas, can’t easily move, and are highly sensitive to change. They also often share habitats, so we get entire groups of highly at-risk invertebrate species hanging on in remnant islands of habitat (known as “centres of endemism”).

Many of these at-risk invertebrates are also members of ancient lineages which stretch back millions of years. They would have survived through a world with dinosaurs and the arrival of mammals. Now, they have met a world with humans.

George Gibbs

How can we stop invertebrate extinctions?

Currently, conservation priorities in Australia are informed by formal listings of individual threatened species. It’s an important conservation mechanism, but it fails the vast majority of invertebrate species.

We just don’t have enough data, evidence or resources to list each one. As a result, most imperilled invertebrates are excluded from protection.

Our results are a wake-up call.

Preventing extinctions of invertebrate species is a formidable challenge. A first step is for everyone to be aware of the huge distortion in conservation efforts and awareness, and the likely magnitude of invertebrate extinctions.

We can help lower the rate of invertebrate extinctions, but it will take a shift in thinking.

To provide better protection across all of Australia’s biodiversity, we need to better protect centres of endemism and better control key threats (such as habitat destruction and broad-scale use of insecticides).

Governments and research organisations must give more priority to taxonomic research – the naming and describing of new species. We also need more comprehensive monitoring by government agencies, conservation groups and citizen scientists of invertebrate populations, to identify new threats as they arise and to protect species and places.

In 2022, Australia signed the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. It joined 196 countries pledging a commitment to zero new extinctions.

If Australia is losing one to three invertebrate species per week, the “zero extinctions” goal is pushed into a whole new realm of accountability. Unless we address this decline, that pledge of zero extinctions is destined to failure.

Michael G. Rix, Queensland Museum

The authors would like to acknowledge the co-authors of this research: Michael Braby, Australian National University; Heloise Gibb, La Trobe University; Mark Harvey, Western Australian Museum; Sarah Legge, Charles Darwin University; Melinda Moir, Western Australia Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development; Brett Murphy, Charles Darwin University; Tim New, La Trobe University; and Michael Rix, Queensland Museum.