The scent and smoke and sweat of a casino are nauseating at three in the morning.

With these opening words, Ian Fleming (1908-64) introduced us to the gritty, glamorous world of James Bond.

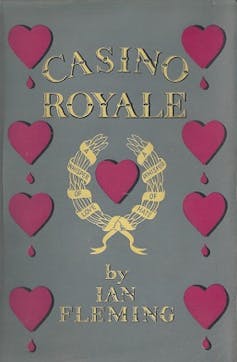

Fleming’s first novel, Casino Royale, was published 70 years ago on April 13 1953. It sold out within weeks. British readers, still living with rationing and shortages after the war, eagerly devoured the first James Bond story. It had expensive liquor and cars, exotic destinations, and high-stakes gambling – luxurious things beyond the reach of most people.

The novel’s principal villain is Le Chiffre, the paymaster of a French trade union controlled by the Soviet intelligence agency SMERSH. After losing Soviet money, Le Chiffre takes to high-stakes gambling tables to recover it. Bond’s mission is to play against Le Chiffre and win, bankrupting both the Frenchman and the union.

The director of British intelligence, known only by his codename “M”, also assigns Bond a companion – Vesper Lynd, previously one of the agency’s assistants. The two infiltrate the casino, play at the tables, and dodge assassination attempts, while engaging in a dramatic battle with French communists, the Soviets, and each other.

Fleming’s Bond – the sophisticated, tuxedo-clad secret agent – is an enduring image of espionage. Since 1953, martinis, gadgets, and a licence to kill have been part of how ordinary people understand spycraft.

Some of this was real: Fleming drew on his own work as a spy for his novels. Intelligence work is often less glamorous than he depicted, but in both espionage and novel-writing, the difference between fact and fiction is not always easy to distinguish.

Ian Fleming, Agent 17F

Fleming came from a wealthy, well-connected British family, but he was a mediocre student. He only lasted a year at military college (where he contracted gonorrhoea), then missed out on a job with the Foreign Office. He could write, though. He spent a few years as a journalist, but drifted purposelessly through much of the 1930s.

The outbreak of war in 1939 changed everything. The director of British Naval Intelligence, Admiral John Henry Godfrey, recruited Fleming as his assistant. Fleming excelled, under the codename 17F. He didn’t see much of the war firsthand, but was involved in its planning. He was an ideas man, not overly concerned with practicalities or logistics. Fleming came up with the fictions; other people had to turn them into realities.

In 1940, for example, he developed “Operation Ruthless”. To crack the German naval codes, Fleming planned to lure a German rescue boat into a trap and steal its coding machine. They would obtain a German bomber, dress British men in German uniforms, and deliberately crash the plane into the channel. When the German rescue crew arrived, they would shoot them and grab the machine.

Preparations began but Fleming’s plan never eventuated. It was too difficult and risky – not least because crashing the plane might simply kill their whole crew.

IMDB

Fleming worked on various operations. When he began writing after the war, these experiences found their way into Bond’s world. Fleming and Godfrey had visited Portugal, a neutral territory teeming with spies, where they went to the casino. Fleming claimed he played against a German agent at the tables, an experience that supposedly inspired Bond’s gambling battles with Le Chiffre in Casino Royale.

Godfrey maintained that Fleming only ever played against Portuguese businessmen, but Fleming never let facts get in the way of a good story.

Fleming picked up inspiration everywhere. Godfrey became the model for M. Fleming’s secretary, Joan Howe, inspired Moneypenny. The Soviet SMERSH coding device in From Russia, With Love (1957) was based on the German Enigma machine. Many of Fleming’s characters were named for real people: one villain shares a name with Hitler’s Chief of Staff, another with one of Fleming’s schoolyard adversaries.

It became something of a sport to hypothesise about the inspiration for Bond. Fleming later called him a “compound of all the secret agents and commando types” he met during war. There were elements of Fleming’s older brother, an operative behind the lines in Norway and Greece. Fleming also pointed to Sidney Reilly, a Russian-born British agent during the First World War. He had access to reports on Reilly in the Naval Intelligence archive during his own service.

Other possible models include Conrad O’Brien-ffrench, a British spy Fleming met while skiing in the 1930s, and Wilfred “Biffy” Dunderdale, MI6 Station Chief in Paris, who wore handmade suits and was chauffeured in a Rolls Royce. Stories of discovering the real-life James Bond still appear.

But there was also much of Fleming himself in Bond. He gave 007 his own love of scrambled eggs and gambling. Their attitude towards women was similar. They used the same brand of toiletries. Bond even has Fleming’s golf handicap.

Fleming would play with this idea, teasing that the books were autobiographical or that he was Bond’s biographer. Much like a cover story for an intelligence officer, Bond was Fleming’s alter-ego. He was anchored in Fleming’s realities – with a strong dash of creative licence and a little aspiration.

Ahmet Baran/AP

The changing world of Bond

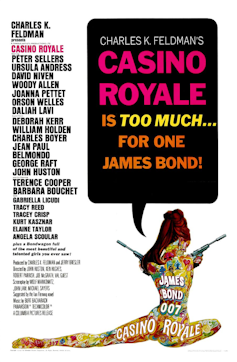

The success of Casino Royale secured contracts for more Bond novels. In the early 1960s, critics began to denounce the books for their “sex, snobbery, and sadism”. Bond’s attitude toward women, in particular, was clear from the beginning. In Casino Royale, he refers to the “sweet tang of rape” in relation to sex with his MI6 accomplice and paramour Vesper Lynd.

But the public appeared to be less concerned. Bond novels still sold well, especially after John F. Kennedy listed one among his top ten books. The first film adaptation, Dr. No, appeared in 1962 and Fleming’s success continued apace.

Bond’s world was evolving, though. From Casino Royale to For Your Eyes Only (1960), Bond battled SMERSH, a real Soviet counter-espionage organisation. The early Bond novels were Cold War stories. Soviet Russia was the West’s enemy, so it was Bond’s.

But East-West relations were thawing in 1959 when Fleming was writing Thunderball (1961). The Cold War could plausibly have ended and he didn’t want any film version to look dated, so Fleming created a fictional villain: SPECTRE. This was an international terrorist organisation without a distinct ideology. It could endure beyond the battles of the Cold War – and did. It features in the 2021 Bond film No Time To Die.

Fleming’s more fantastic plots were always anchored in reality by recognisable brands and products. Bond’s watch was a Rolex; his choice of bourbon was Jack Daniels. His cigarettes were Morlands, like Fleming’s. In the novels, Bond drove Bentleys – the Aston Martin was introduced in the 1964 film Goldfinger.

The films have changed Bond’s brands to keep up with the world around them (and secure lucrative product-placement deals): Omega replaced Rolex in Goldeneye (1995); the martini was swapped for a Heineken in Skyfall (2012). Bond now carries a Sony phone.

Other changes brought the 1950s spy into the 21st century. Recent films have more diverse casting. Their female characters do more than just spend a night with Bond before their untimely deaths. The novels, too, continue to change – the 70th-anniversary editions have had racial slurs and some characters’ ethnic descriptors removed.

Some have criticised this as censorship. But as with recent rewritings of Roald Dahl’s books, changes like this are not new. Fleming’s family has defended the alterations by citing similar removals in 1955, when Live and Let Die was first published in the United States.

There is a risk that this whitewashes Fleming’s attitudes, making them appear more palatable than they really were. But the revised Bond novels will include a disclaimer noting the removals. Casino Royale itself has not been altered (Bond’s rape comment remains intact), so the changes will perhaps be less extensive than the media coverage suggests.

Is James Bond a misogynist? He doesn’t have to be Connery, Moore or even Craig’s vision forever

Spies After Bond

Fleming is not the only ex-spy to have successfully turned his hand to spy fiction. John le Carré’s George Smiley is perhaps an anti-Bond: slightly overweight, banal, and essentially a bureaucrat. He relies on a shrewd mind rather than gadgets or guns.

Le Carré introduced his readers to a more mundane, morally grey world of espionage. He had worked for MI5 and MI6 in the 1950 and ‘60s. He thought Bond was a gangster rather than a spy. Le Carré’s stories have also shaped how we think about espionage. Words like “mole” and “honeytrap” – the terminology of spycraft – entered common usage via his novels.

IMDB

Stella Rimington, the first female director-general of MI5, began writing fiction after retiring from intelligence in the late 1990s. Her protagonist, 34-year-old Liz Carlyle, hunts terror cells in Britain. Like Smiley, Carlyle appears rather ordinary. She is serious and conscientious. We get glimpses of the everyday sexism she experiences. Carlyle triumphs by remaining level-headed, not by fiery gun battles or explosions.

After three decades of agent-running for the CIA, Jason Mathews wrote his Red Sparrow trilogy to occupy himself in retirement. He called it a form of therapy.

There’s a little more Bond in Mathews’ books than in those of le Carré or Rimington. His protagonists Nate Nash and Dominika Egorova are attractive, charismatic and entangled in a personal relationship of stolen moments and high drama. This is counterbalanced by the many hours they spend running surveillance-detection routes before meeting targets. The more tedious and banal aspects of spycraft – brush passes, broken transmitters, and dead drops – accompany the glamour and romance.

John le Carré, MI6 and the fact and fiction of British secret intelligence

The wilderness of mirrors

Spy fiction is never just about entertainment. The real world of espionage is so secret that most of us only ever encounter it on pages or screens. We don’t usually look to Bond films for accurate representations of espionage. But the influence of Fleming’s spy and the general aura of secrecy surrounding intelligence work lend some glamour and excitement to the work of real spies.

These fictions also influence our views on real intelligence organisations, their activities, and their legitimacy. This is why the CIA invests time and money into fictionalisations dealing with its work. From stories based on true events, such as Argo (2012) or Zero Dark Thirty (2012), to fictional series like Homeland (2011-20), the agency’s image is shaped via the media we consume.

This was true when Fleming was writing, too. Soviet authorities were preoccupied by Sherlock Holmes’ surging popularity behind the Iron Curtain and fretted over the release of the Bond novels and films. The KGB studied both carefully. It was likely Bond who prompted KGB officers to release classified details about their most successful spy story: the career of Richard Sorge.

Former intelligence officers such as Fleming are often quite good at fiction – perhaps because it is a core part of spycraft. A solid cover story has to be grounded in reality, with just enough fiction to protect the truth or gain a desired outcome. A good operation often requires creativity, to outwit a target or evade detection. And spreading fictions – disinformation – can sometimes be just as useful as gathering information.

The world of espionage is sometimes referred to as the “wilderness of mirrors”. Spycraft relies on both reflections and distortions. The line between fact and fiction, between real stories of intelligence work and invented ones, can become blurry – and intelligence agencies often prefer it that way.