People around the world see various factors as contributing to economic inequality in their country:

- Majorities in almost every country surveyed believe all six factors we asked about lead to economic inequality at least a fair amount. However, there are differences over whether each contributes a great deal.

- In 31 of 36 countries, more say that rich people having too much political influence leads to economic inequality than say this about any other factor.

- A median of 48% of adults say problems with their country’s education system contribute a great deal to economic inequality.

- Around four-in-ten say some people being born with more opportunities than others (40%) and some people working harder than others (39%) are factors that contribute a great deal.

- Fewer point to the impact of robots and computers doing the work previously done by humans (31%) or to discrimination against racial or ethnic minorities (29%).

Rich people’s political influence

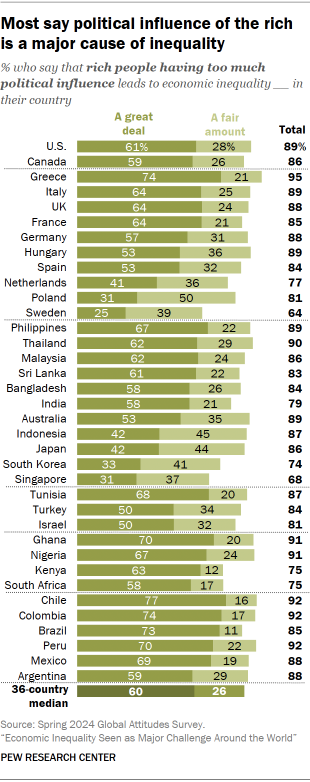

A median of 60% across 36 countries say that rich people having too much political influence leads to economic inequality a great deal in their country. Majorities hold this opinion in 31 nations and in at least one country every region surveyed.

The view that the political influence of the wealthy contributes to economic inequality, while common across most survey countries, is particularly widespread in Latin America. About seven-in-ten or more say this factor contributes a great deal in five of the six Latin American countries polled.

Similarly large shares hold this view in Ghana, Greece, Nigeria, the Philippines and Tunisia.

By comparison, only about a third of adults or fewer in Poland, Singapore, South Korea and Sweden say rich people’s political influence contributes a great deal to economic inequality in their country.

Views by ideology

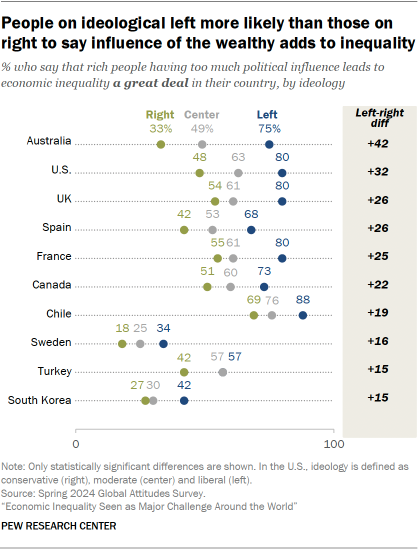

In 10 countries, people who place themselves on the ideological left are more likely than those on the right to believe that rich people’s political influence is a major contributor to economic inequality.

The ideological divide is particularly stark in Australia, where 75% of people on the left say this factor leads to economic inequality, compared with a third of those on the right. And in the U.S., 80% of liberals hold this view, compared with 48% of conservatives.

Problems with the education system

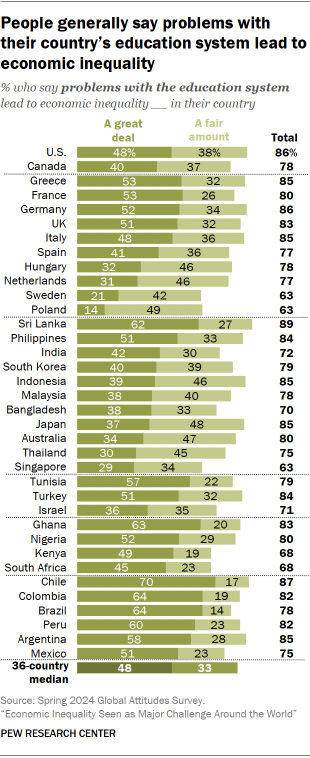

A median of 48% of adults across the countries surveyed think problems with their nation’s education system lead to economic inequality a great deal. Another 33% say this factor contributes a fair amount.

About half or more of the public in the U.S. and several European countries (France, Germany, Greece, Italy and the UK) see this as a major contributor to economic inequality. Fewer Swedish and Polish adults say the same.

Of the Asia-Pacific nations polled, concerns about the education system are strongest in Sri Lanka – one of just two countries where this is seen as the top contributing factor of the six we asked about. Across the rest of the Asia-Pacific survey countries, concerns about education are less common.

In the Middle East-North Africa region, a majority of Tunisians and about half of Turks see problems with education as a major contributor to inequality. Turkey is the other survey country in which education is seen as the top factor.

Across the sub-Saharan African countries polled, about half or more in Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria say education problems contribute a great deal, compared with fewer than half in South Africa.

And as with other possible causes of inequality included in the survey, concerns about education are especially strong in Latin America. The share of adults who say these problems contribute a great deal to economic inequality ranges from 70% in Chile to 51% in Mexico.

Views by education

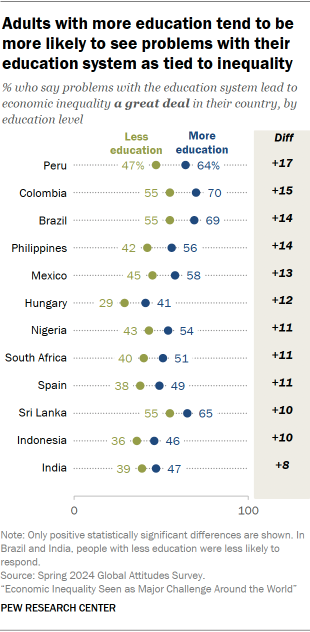

In 12 nations – most of which fall in the middle-income category – adults with more education are more likely than those with less education to say that problems with the education system contribute a great deal to economic inequality. For example, about two-thirds of Peruvians with more education (64%) express this view, compared with 47% of Peruvians with less education.

There are sizable gaps by education in three other Latin American countries surveyed: Brazil, Colombia and Mexico (though Brazilian adults with less education are also less likely to provide a response).

Views by ideology

In nine countries, adults on the ideological left are more likely than those on the right to say education problems contribute a great deal to inequality in their country.

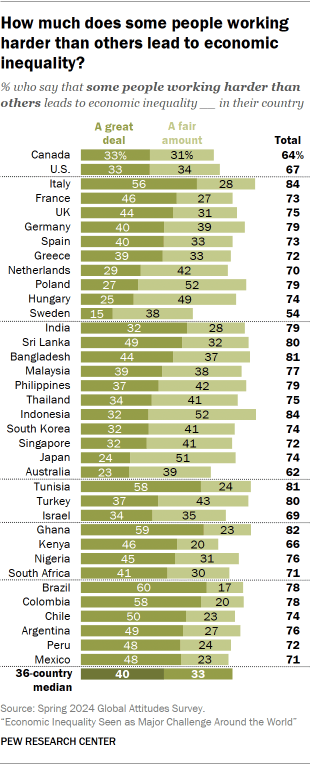

Some people working harder than others

A median of 40% across 36 countries believe that some people working harder than others leads to economic inequality a great deal. A median of 33% say this contributes a fair amount.

In the U.S. and Canada, only a third say differences in work ethic contribute a great deal.

Opinions vary significantly in Europe. A 56% majority of Italians say this is a major contributor to economic inequality, but just 15% of Swedes share this opinion.

In the Asia-Pacific region, about half of adults in India and Sri Lanka see a strong connection between inequality and some people working harder than others. Across the other survey countries in the region, the share of adults who hold this view ranges from 44% in Bangladesh to 23% in Australia.

In the Middle East-North Africa region, Tunisians are the most likely to say work ethic is strongly connected economic inequality: 58% hold this opinion, compared with 37% of Turks and 34% of Israelis.

Ghanaians stand out among the sub-Saharan Africans surveyed. A 59% majority of adults in Ghana say some people working harder than others contributes a great deal to inequality, while fewer in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa agree.

Views by education

In 12 countries, people with less education are especially likely to say that some people working harder than others contributes a great deal to economic inequality. This pattern is particularly stark in Italy, where 59% of those with less education believe this, compared with 42% of Italians with more education.

Views by social class

In 11 countries, people who place themselves in the working or lower social class are more likely than those in the upper or upper middle class to believe that some people working harder than others leads to economic inequality (we measure class by asking respondents which social class they identify with – this may or may not correspond to measures of income, occupation or education). For example, 54% of Argentine adults who identify with lower social classes believe this, compared with 33% of Argentine adults who identify with upper social classes.

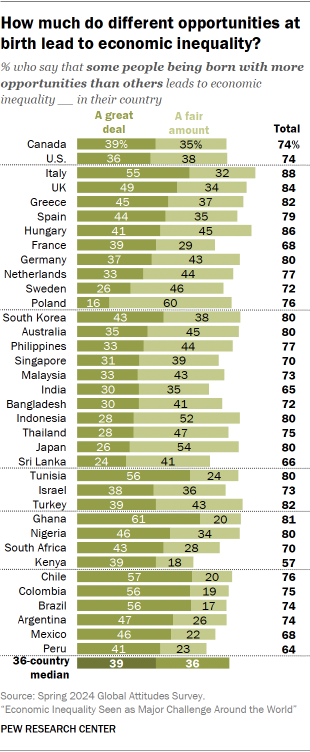

Some people being born with more opportunities than others

A median of 39% of adults across the countries surveyed say that some people being born with more opportunities than others leads to economic inequality a great deal. A median of 36% say it contributes a fair amount.

Like views of people working harder than others, this sentiment is again generally strongest in Latin America, where roughly half or more in four of the six countries polled (Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Colombia) see a strong connection between economic inequality and opportunities at birth.

Majorities in Ghana, Italy and Tunisia also say this contributes a great deal to economic inequality.

Elsewhere – such as in Indonesia, Japan, Poland, Sri Lanka, Sweden and Thailand – only about a quarter of adults or fewer say this contributes to inequality in their country.

Views by ideology

In 14 countries, people on the ideological left are more likely than people on the right to say different opportunities at birth lead to inequality. In the U.S., for example, 58% of adults on the left say this factor contributes a great deal, compared with 21% of those on the right.

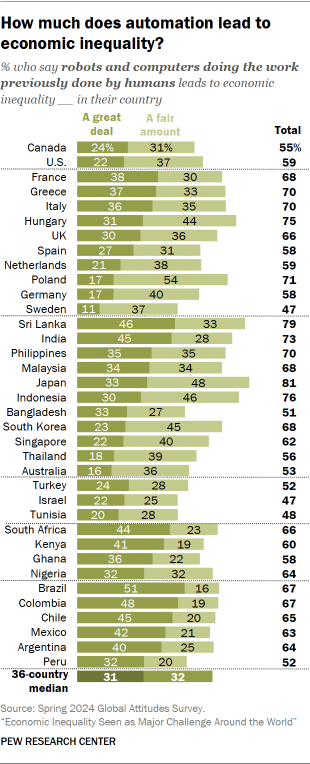

Robots and computers doing the work previously done by humans

Compared with the other factors we asked about, somewhat fewer people say that robots and computers doing work previously done by humans leads to economic inequality a great deal or a fair amount in their country. A median of 31% say this contributes a great deal to inequality, while a median of 32% say it contributes a fair amount.

About half of adults in Brazil and Colombia say robots and computers doing the work of humans strongly contributes to economic inequality – the highest shares measured on this question.

Across most of the other countries surveyed, about four-in-ten or fewer see automation as strongly linked to economic inequality. In fact, people across many countries give this factor the lowest rating of the six included in the survey.

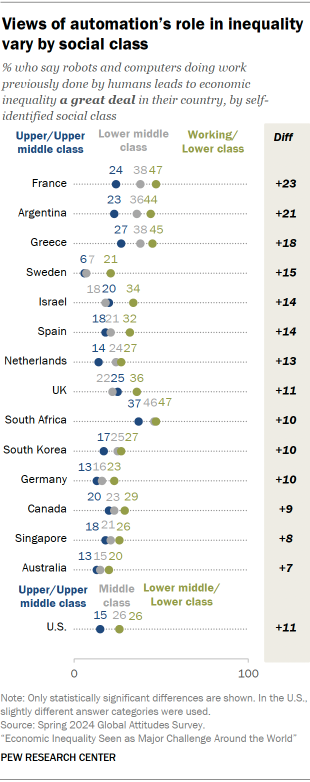

Views by social class

People who describe themselves as belonging to the working or lower social class are more likely than those in the upper or upper middle class to say technology replacing people contributes a great deal to economic inequality.

The gap is widest in France, where 47% of those who identify with lower classes say automation adds to inequality, compared with 24% of those who identify with upper classes. Double-digit differences also appear in Argentina, Germany, Greece, Israel, Netherlands, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and the UK.

In the U.S. – where we had slightly different answer categories for social class – 26% of adults who describe themselves as belonging to the lower middle or lower class say automation contributes a great deal to inequality, compared with 15% of those who describe themselves as upper or upper middle class.

Views by education

In 10 countries, people with less education are more likely than those with more education to say automation contributes a great deal to economic inequality.

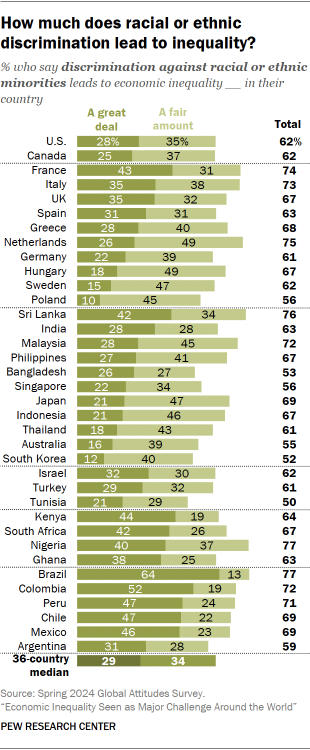

Discrimination against racial or ethnic minorities

In general, fewer people around the world say racial or ethnic discrimination leads to economic inequality than say the same of the other issues we asked about. A median of 29% of adults across the countries surveyed say that discrimination against racial or ethnic minorities contributes a great deal to economic inequality in their country. A median of 34% say it contributes a fair amount.

Brazilian adults are particularly likely to say racial discrimination is a major contributor to economic inequality: 64% hold this opinion, the highest share in any country.

In Latin America more broadly, this sentiment tends to be strong, with 46% to 52% of adults expressing this view in Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru.

Elsewhere, no more than about four-in-ten generally say discrimination contributes a great deal to economic inequality. In a few countries – Australia, Hungary, Poland, South Korea, Sweden and Thailand – fewer than two-in-ten say this.

(For this question, respondents in most countries were asked about discrimination against “racial or ethnic” minorities. In Hungary, Indonesia, Sweden, Tunisia and Turkey, the question used “ethnic.” In India, the question used “caste or ethnic.” In Kenya, the question used “ethnic or tribal.”)

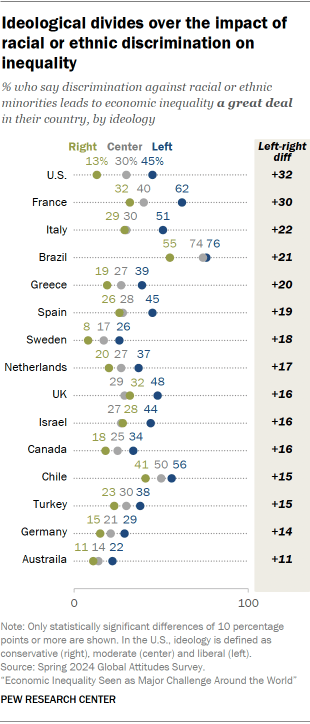

Views by ideology

People who place themselves on the ideological left are more likely than those on the right to say racial or ethnic discrimination against minorities contributes a great deal to economic inequality. This pattern in present in roughly half of the 36 countries surveyed, particularly in high-income countries.

The divide is widest in the U.S., where 45% of liberals say discrimination contributes a great deal to inequality, compared with 13% of conservatives. Left-right differences of 20 percentage points or more are also present in Brazil, France, Greece and Italy.

Views by race and ethnicity

Views differ by race and ethnicity in several countries. Black Brazilians are 16 points more likely than White Brazilians to say discrimination contributes to economic inequality. And Arab Israelis are more than twice as likely as Jewish Israelis to say this (56% vs. 26%).

In the U.S., Black Americans (57%) are much more likely than Hispanic (37%) or White (20%) Americans to say discrimination adds to inequality.